Samya and Omayya Abu Watfa lost their father eleven years ago. They are preparing for the new term at university, where Samya is studying chemistry and Omayya is studying food security. Each one needs between $1,100 and $1,200 for tuition fees but are dependent on their brother Mohammad, 33, who is a fisherman. That means money is in short supply.

“He has been working day and night to provide for us, our mother and three brothers,” Samya told me. Mohammad is our brother, father, everything to us.” He also has his own family to think of; his wife and four children.

Mohammad Abu Watfa inherited his boat from his father when he was 22. He left university in order to work and provide for his family. “I worked with my father when he was alive, even while studying. He wanted me to become an engineer, but I could not work and continue my studies.”

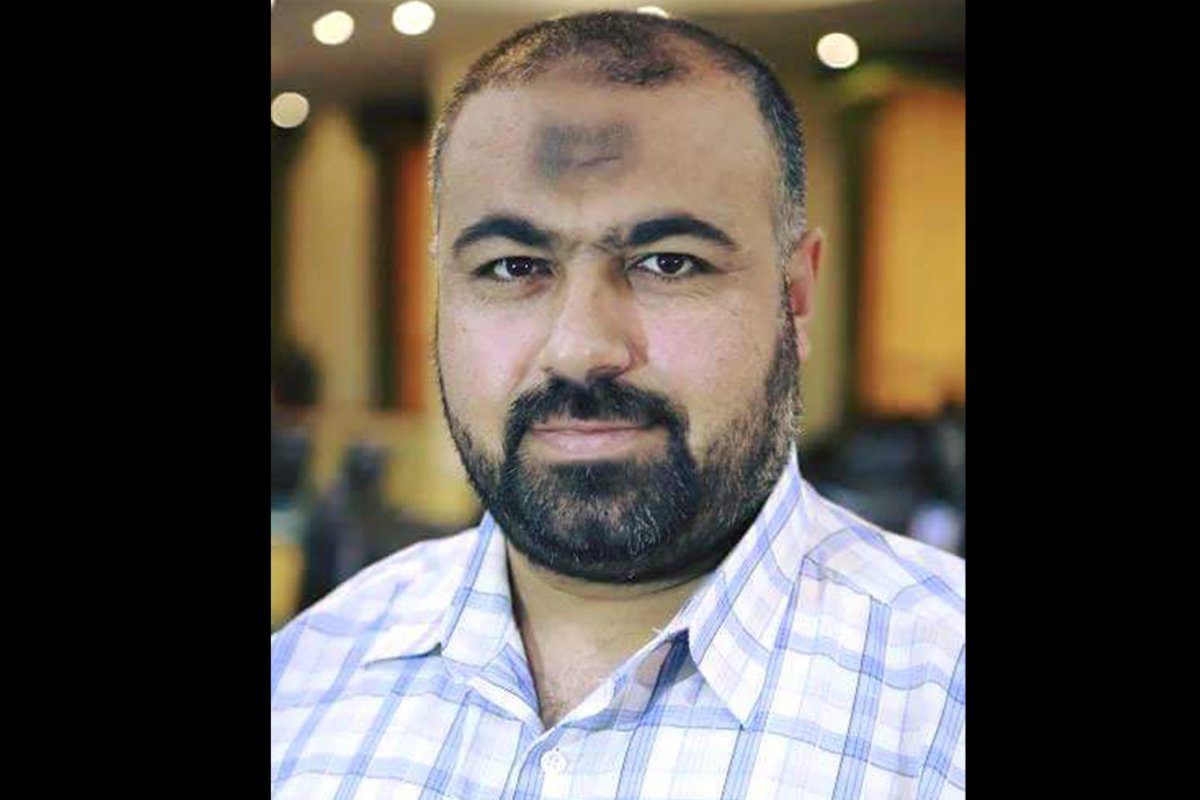

Nizar Ayyash

Like all the other fishermen in Gaza, Abu Watfa would be happy with his work — although it is very hard — if not for the restrictions imposed by Israel and the daily violations against them by the Israeli navy.

The head of the Fishermen’s Syndicate in Gaza pointed out that the Israeli occupation has imposed a strict land, air and sea blockade on the Gaza Strip since 2006. “This makes the life of more than 2 million people in Gaza unbearable,” said Nizar Ayyash. “Fishing is one of the sectors most affected by the blockade. More than 4,500 fishermen, who collectively have around 50,000 dependants, have lived and worked under extreme pressure and stress due the Israeli measures related to the blockade.”

According to the Oslo Peace Accords signed in 1993 between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organisation, the Palestinians should have unrestricted access for fishing up to 20 nautical miles off the Gaza coast. However, they have never been allowed to venture more than 16 miles. Normally, they are restricted to 12 miles; often it’s much less.

Last week, for example, the Israeli occupation navy reduced the fishing zone to six nautical miles in response to what Israel said was the firing of incendiary balloons from Gaza towards Israel. It was then extended back to 12 nautical miles. This has been the Israeli game with the Palestinian fishermen since 2005. There are times when the occupation state bans fishing altogether for days or weeks on end under the flimsiest of pretexts.

“Since 2007,” said the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA) in a recent report, “Israel has maintained a fluctuating fishing zone as part of its maritime ‘buffer zone’ policy — i.e., the no-go military areas unilaterally imposed by Israel on Palestinian waters — which often completely prohibits fishing for Palestinians.”

Mohammad Abu Watfa

Fishing has always been dangerous work for men like Abu Watfa, who puts his life on the line in order to put food on the table at home. “Sometimes there are fish around 15 miles offshore. If we want to catch them we have to go beyond that and drive them towards the shore. When we do, the Israeli navy chase us, fire at us and then ban us from fishing.”

UNOCHA pointed out that, “Over the years, Israel’s unlawful and unwarranted attacks — that include lethal and other excessive force, arbitrary arrest, and confiscation and destruction of boats and other fishing materials — and punitive restrictions against Palestinian fishers, have made fishing off Gaza’s coast a risk to life and safety and pushed the fishing community into extreme poverty.”

These practices, added the UN, are part of Israel’s ongoing closure policy over the Gaza Strip. “This amounts to an unlawful collective punishment of the more than two million Palestinian residents, and are among the practices, laws and policies that constitute Israel’s apartheid regime against the Palestinian people.”

Bilal Bashir, 42, works alongside ten other fishermen on the same boat. He complained about the repeated Israeli aggression against them. “Sometimes, Israel decides to reduce the fishing zone while we are actually at sea. We only know about the restriction when the navy opens fire at us or the sailors scream at us through loudspeakers.”

His boat has been hit several times by Israeli fire. In March, 2015, he recalled bitterly, his colleague Tawfiq Abu Riala, 32, was killed. “We were shocked and called for help when Tawfiq was hit. Instead of helping us, the navy arrested two other men.”

READ: Besieged Gaza is living in a boiling pot

The last such incident was in February 2018. The occupation forces explained what happened: “A suspicious [sic] ship left the fishing zone off the northern Gaza Strip, with three suspects on it [prompting Israeli sailors to conduct] the arrest protocol, which included calls [to stop], warning shots in the air and shots at the boat itself… As a result of the gunfire, one of the suspects was seriously injured and later died of his wounds.”

Bilal Bashir

Fishing is an expensive business. One day at sea can cost up to $1,500 for one boat with ten fishermen on board. “When we sail for 15 nautical miles, our catch can hardly cover the expenses,” noted Kinan Baker, 27. “When the fishing zone is reduced to six nautical miles, we make a huge loss because the catch doesn’t cover our expenses.”

Ayyash described the fishing industry as the most vulnerable sector under the Israeli occupation siege imposed on Gaza. “Israel exploits everything to put pressure on the Palestinian resistance. This [collective punishment] is a clear violation of international law.” The union chief called for the world to put pressure on Israel to stop putting the lives and livelihood of fishermen in danger for political or security reasons.

“Collective punishment amounts to war crimes and, as part of a widespread or systematic policy, crimes against humanity, and are the main drivers of the deteriorating humanitarian situation in Gaza,” added Al Mezan Centre for Human Rights.

Kinan Baker

In June last year, the World Bank said that “fishing is a vital source of employment, with more than 100,000 people benefiting from the sector.” Aside from the fishermen and their families, it named retailers, restaurant owners, hatchery operators and fish transporters as beneficiaries of the industry. “Still, the sea is not as bountiful as it once was. The people of Gaza cannot depend on, or at times even afford, their own fish. Most fishing families are poor, and their income is becoming increasingly unreliable as marine ecosystems continue to degrade.”

Life for a fisherman is always hard, everywhere, but under Israel’s military occupation it is even harder. The fishermen of Gaza are caught between the rock of the occupation and the hard place of economic difficulties.