Meeting 12-year-old schoolgirl Maram Al-Amawi and her mother Ezdihar, 31, was an emotional moment. I was with them to hear about their treatment for the severe burns that they received when an explosion and fire ripped apart a bakery in Al-Nuseirat refugee camp in the Gaza Strip last year.

Maram and her mother were outside the bakery waiting for a taxi to go home with food that they had bought from the market. “Suddenly, we heard an explosion and a massive fireball appeared from the bakery,” explained Ezdihar. “My clothes caught fire and I started running with my daughter. I did not let go of her hand until I fell unconscious.”

The blaze, which investigators said was caused by a gas leak, destroyed the bakery and several shops around it. Twenty-five people were killed, and dozens more were left with severe burns, including Ezdihar and Maram, who remained conscious throughout her ordeal and was able to provide a detailed narrative of the incident.

Mother and daughter were admitted to the hospital and spent months in the burns unit. Their treatment is ongoing.

Oppression and racism: The main determinants of Jewish immigration

Treatment challenges

Treatment for serious burns is a challenge everywhere, but in the Gaza Strip, which has been under an Israeli-led siege for 15 years, it takes on an even more difficult dimension. Hospitals have chronic shortages of drugs and medical disposables, and equipment often breaks down due to a lack of proper maintenance. Repairs are not always possible because spare parts are blocked or delayed by the Israeli siege. The hospitals are also frequently overrun by casualties from Israel’s military offensives and incursions.

Medical charity Médecins Sans Frontières has an office in Gaza which is at the forefront of the efforts to overcome these challenges. MSF’s Mohammad Qatarawi told me about the organisation’s efforts to treat Palestinians in Gaza, including burns patients like Ezdihar and Maram.

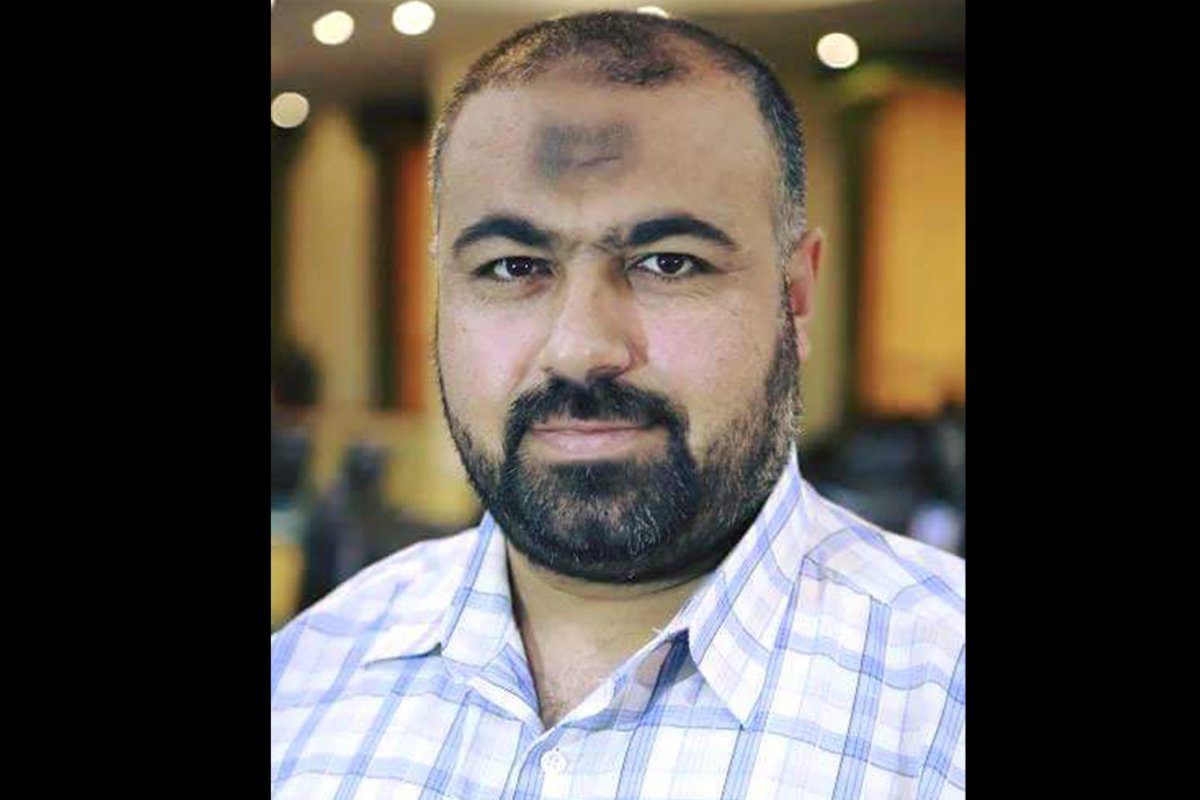

Qatrawi working to exporting measurements to Abu Matar to make the printing

“Last year’s bakery blaze shocked everyone in Gaza due to the massive number of casualties,” said Qatarawi. “It left a very large number of people with severe burns and that pushed us to double our efforts to cover the needs of every single case, especially those with facial burns.”

The particular challenges facing MSF’s operation in Gaza, he pointed out, include the lack of proper equipment needed for treatment. “For example, the transparent plastic masks developed by MSF which we order from abroad take months to be delivered.”

READ: After killing Muslim women, the international community cannot teach us how to treat them

However, in the centre of Gaza City, near the rubble of a building destroyed by Israeli bombs in May, Mohamad Abu Matar, 34, is now busy making transparent face masks. The MSF calls this a “blessing”, because long delivery delays may now be a thing of the past.

“We were trained to scan faces and take the measurements for 3D-printed masks,” said Qatarawi, “but we had to wait for months to get them from abroad. Now they are being made locally, here in Gaza.”

Abu Matar’s masks have already been used to help several patients. And they have been successful.

“I was fortunate to have this mask,” said Ahmad Sabbah, 30, who suffered critical burns in the bakery blaze last year. “I need more time to recover completely. The MSF team told me that this mask would help me to alleviate the dreadful impact of the burns.”

The Gaza phoenix

During the Israeli bombing of Gaza in May, Abu Matar’s shop where he made the masks was in one of the buildings destroyed. His dreams were shattered. “It is was not easy to lose my project in the blink of an eye. I was at home and heard the news about the intensive bombing of Al Wahda area in Gaza, near my shop. Then I heard that the building where my shop was located was also bombed. It was a hard moment for me.”

Palestinians grow up learning to overcome the challenges imposed on them by Israel and its brutal military occupation. Abu Matar is the embodiment of Palestinian persistence. “I decided to rise from the rubble,” he told me. “Like the mythical phoenix. The Gaza phoenix. I had to, because everything I had was destroyed.”

Abu Matar, new shop

He rented a new shop and found the finance to get everything he needed to continue making 3-D masks. “I made the parts for the printer on my own, assembled them and started operating again. It gives me the same precise output as the machine destroyed by the Israelis.” Such was the demand after the Israeli offensive that he made several more printers to boost his production level.

Planting hope

Abu Matar is now experimenting to make spare parts for medical equipment which are not allowed by Israel to be imported by the Palestinians in Gaza. “So far, I have been able to produce parts for prosthetic limbs. They are being tested together with others involved in this field.”

Abu Matar’s hope is to be able to help amputees in the same way that his work helps those with facial burns. “This mission seems more like humanitarian work than a profitable business.” It is much appreciated, nonetheless.

Abu Matar

MSF’s Mohammad Qatarawi is clear on this matter: “There is no doubt that Abu Matar really facilitated our job.” As far as burns patient Ahmad Sabbah is concerned, “MSF gave me hope for treatment, and Abu Matar gave me hope for my recovery.”

Ezdihar Al-Amawi and her daughter Maram also have cause to be grateful to Abu Matar and his 3D-printed face masks. Both use the masks and know that they play an important role in their treatment and recovery.

Happily, Abu Matar is now able to make 3D-printers for commercial use that could be used for manufacturing spare parts for many things, including vehicles as well as medical equipment and essential medical machines. There is already talk of selling the printers to allow people to start their own businesses. He is thus not only helping seriously injured patients, but also in a position to ease the chronic unemployment in the besieged Gaza Strip, albeit in a small way. The Gaza phoenix is indeed rising.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Monitor.