The Serbian member of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s joint presidency council warned earlier this month that the Serbs of the multi-ethnic European country would leave the federation if the government failed to resolve the challenging political situation. “It is inevitable that Bosnia and Herzegovina will break up and Republika Srpska would leave the country if we cannot overcome the difficult situations we are in,” warned Milorad Dodik.

This was not the first time that Dodik has made a comment which hints at his plan to take the Serb-dominated territories out of the federation. The US, the West and other powers have condemned these remarks and called for Dodik to retract them, but instead, he has taken several measures on the ground.

It was almost 30 years ago, in 1992, when ethnic differences ignited a fierce civil war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. After its secession from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1991, the multi-ethnic Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina passed a referendum for independence on 29 February, 1992 and gained international recognition.

According to a 1991 census, the country was inhabited mainly by Muslim Bosniaks (44 per cent), Orthodox Serbs (32.5 per cent) and Catholic Croats (17 per cent). In the aftermath of independence, “Bosnian Serb forces, with the backing of the Serb-dominated Yugoslav army, perpetrated atrocious crimes against Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) and Croatian civilians, resulting in the deaths of some 100,000 people (80 per cent of them Bosniak) by 1995.”

OPINION: Srebrenica 25 years on, and reconciliation seems impossible

Ending the civil war was not easy. An arms embargo was imposed on the Bosnian Muslims, while the Serbs had access to the Yugoslav army’s weapons. In 1993, the UN peacekeeping forces declared that the towns of Srebrenica, Zepa and Gorazde were “safe havens” and ordered all Muslims to disarm. However, following the Srebrenica Massacre in 1995, when women were raped or sexually assaulted, and between 7,000 and 8,000 men and boys were killed by Serbs in full view of Dutch UN peacekeeping troops, the Bosniaks were obliged to accept the US and EU-backed Dayton Accords agreed in Dayton, Ohio, which created the federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The United States and others brokered the Dayton Accords and “wrote the country’s new constitution, putting the former warring factions – Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs – on an equal footing to help resolve the tensions that fuelled the conflict.”

![Former US President Bill Clinton (R) meets with Croatian President Franjo Tudjman (2nd R), Bosnian President Alija Izetbegovic (C) and Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic at the US Ambassador's residence in Paris 14 December prior to the signing of the Dayton peace agreement onm Bosnia [LUKE FRAZZA/AFP via Getty Images]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/GettyImages-51994363.jpg?resize=920%2C584&ssl=1)

Former US President Bill Clinton (R) meets with Croatian President Franjo Tudjman (2nd R), Bosnian President Alija Izetbegovic (C) and Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic at the US Ambassador’s residence in Paris 14 December prior to the signing of the Dayton peace agreement onm Bosnia [LUKE FRAZZA/AFP via Getty Images]

The agreement gave Bosniaks and Croats — that is, the majority of the inhabitants — an enclave surrounded by Orthodox Serbs. Dayton did not recognise other small minorities, who make up about 12 per cent of the population. They were excluded from a political role in the country. At least, a quarter of them were Bosniaks.

“Dayton was useful for bringing an end to the war, but not for building a state,” Halid Genjac, general secretary of the Party for Democratic Action (SDA), Bosnia’s largest political party, told Equal Times last year. Genjac, who was a member of the Bosnian negotiating team in Dayton, added: “We are in favour of amending the constitution in line with the ECHR ruling [on the Sejdić and Finci case], but the Croat and Serb representatives are blocking it. Serbs and Croats see the quota system as a safeguard against the potential domination of the political scene by Muslims, who represent more than 50 per cent of the country’s population.”

It is not only the Bosniaks who want to update the Dayton Accords; the Croats do too. Dragan Čović, the president of the Croatian Democratic Union of Bosnia and Herzegovina, said: “Although it has been twenty-five years since the end of the war, we have recently heard certain political representatives in Bosnia and Herzegovina calling for war and secession. This is an irrational approach and must be strongly rejected.”

Čović called for major updates to the Dayton Accords and drastic reforms that promote human rights and cancel discrimination and the humiliation of certain minorities regardless of their religion. He argued that this is needed in order to pull the country out of poverty and stagnation through joining the EU, which initially conditioned membership on major human rights reforms.

The problem is that Dodik and his supporters have been using Islamophobic claims in order to scare the EU and the Serbs about the Bosniaks. He has claimed several times that there are Daesh members in the country, for example. His hate speech has encouraged several attacks on mosques, but the most provocative Serbian action is to celebrate the massacres and genocide of Muslims in the 1990s as national events, glorifying war criminals and naming streets after them.

![US army armored column led by an Abrams M1A1 tank passes next to spectators and reporters as it crosses a dike leading to the Sava River 22 December [MIKE NELSON/AFP via Getty Images]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/GettyImages-51423961.jpg?resize=500%2C329&ssl=1)

US army armored column led by an Abrams M1A1 tank passes next to spectators and reporters as it crosses a dike leading to the Sava River 22 December [MIKE NELSON/AFP via Getty Images]

German politician Christian Schmidt was appointed a High Representative in May by the Peace Implementation Council. VOA reported that he said that Bosnia and Herzegovina “faces the greatest existential threat of the postwar period” and that Republika Srpska authorities, led by Dodik, “endanger not only the peace and stability of the country and the region, but – if unanswered by the international community – could lead to the undoing of the [Dayton] agreement itself.”

DW pointed out that, “Dodik, a former Western protege turned nationalist, has been threatening for years to separate Republika Srpska from the Bosnian state.” Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has also been warning the world about this. The EU and the US, who can deal with the issue if they so wish, are silent about it because the EU most likely does not want to be obliged to accept the membership of a country with a substantial Muslim population.

The EU issued a joint statement recently condemning the ongoing escalations by the Serbs and stressed that this puts the stability of the region in danger. On the ground, though, it maintains a negative silence or tacit support for the Serbs.

“Neither the US nor the EU have been pushing back against increasingly escalating attacks on the unity of Bosnia-Herzegovina over the last several years,” VOA reported German analyst Toby Vogel as saying.

OPINION: Bosnia and Herzegovina’s regional challenges

It is possible that the US and EU do not have enough courage to explain their silence. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has no such qualms, and has made his position very clear: “I am doing my best to convince Europe’s great leaders that the Balkans may be further away from them than from Hungary, but how we manage the security of a state [Bosnia and Herzegovina] in which two million Muslims live is a key issue for their security too.”

Orban simply cannot imagine a Muslim majority country in Europe. His was not just the voice of Hungary, but also of the US and EU members, none of whom criticised him. Gabriel Escobar, the US State Department’s special representative for the Western Balkans, has said that Washington plans to “aggressively use” sanctions against Bosnian politicians, but no concrete actions have yet been taken.

Voice of America reported that the US Treasury imposed sanctions on Dodik in 2017 for obstructing the Dayton Accords, but the EU did not do likewise. There are a lot of things that EU states could do, but the political will simply isn’t there, which should be a warning for the millions of Muslim citizens in countries across the EU and in the United Kingdom.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Monitor.

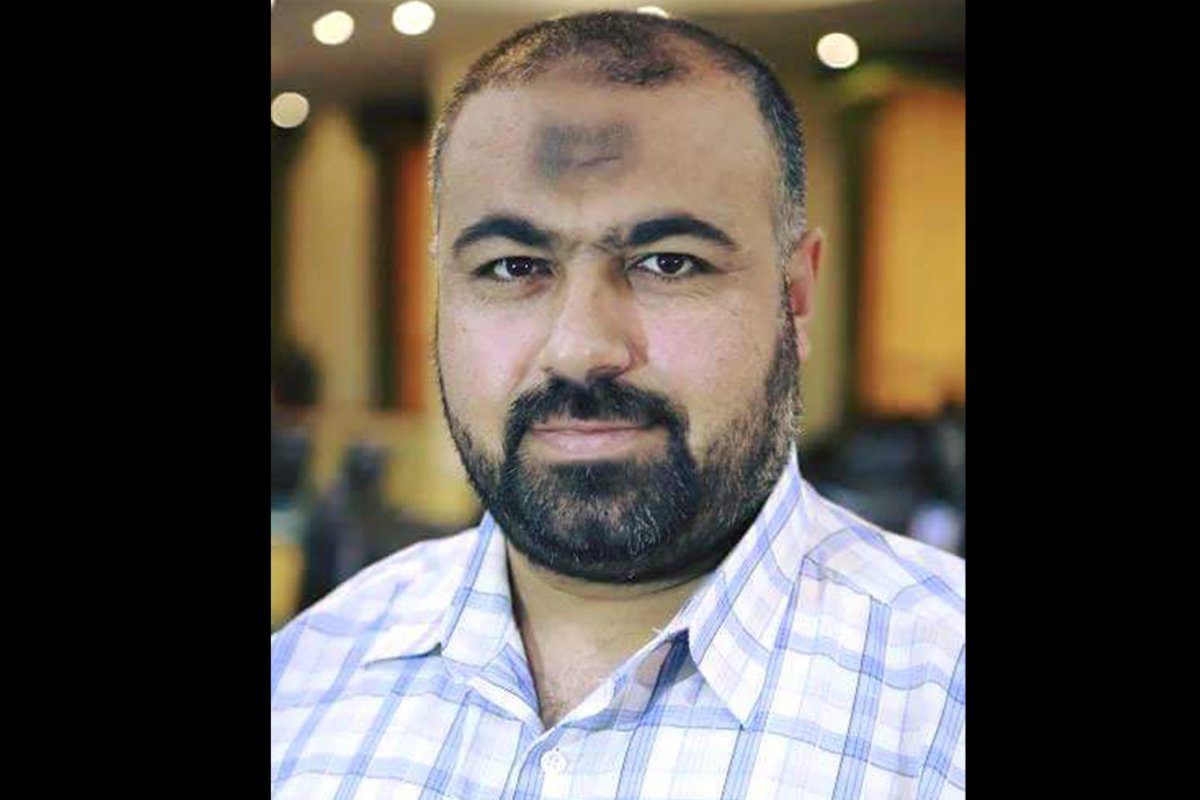

![Chairman of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina Milorad Dodik on September 23, 2021 [ATTILA KISBENEDEK/AFP via Getty Images]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/GettyImages-1235443754-scaled-e1640276058748.jpg?fit=920%2C613&ssl=1)