It was easy during the years of the alliance between the Commanders of the Sudanese Army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), Lieutenant-General Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan and Lieutenant-General Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti), from April 2019 until April 2023, to see the tendency of the military element to cling to power, and not want to hand it over to civilians. The military element treated the Constitutional Charter for the Transitional Period, which specified the details of the military-civilian partnership, as a hostile attack, trying to absorb its first wave, and then put the “enemy” in a long period of exhaustion until the dawn of 25 October, 2021, when the military element acted, arresting civilian leaders and announcing that it alone would rule the country.

The two military Commanders complained, more than once before the coup (during the stage of preparing public opinion to accept military intervention), that “the military element’s authority is a formality”, according to the document agreement, and they were keen to emphasise that holding the military element back from involvement in executive work was the cause of the economic and security crisis. Therefore, the two leaders chose to describe their coup as “correcting the course of the revolution”.

READ: France to host humanitarian conference for Sudan in April

Today, one year after the war, the Army leadership’s desire to rule seems clearer and closer, while the RSF is wandering in an imaginary circle in which it assembles dozens of inconsistent narratives to create an imaginary image of a militia fighting the remnants of the former regime in favour of democratic transformation. However, far from the delusional narratives, the reality is that the RSF, which seized large areas of the country and took control of most of the Sudanese capital, the largest cities and states, did not protect citizens, nor did they provide a model for managing people’s lives, let alone managing a State or quasi-State. On the contrary, the RSF committed violations, war crimes, theft, looting and attacks, with the aim to empty their areas of control of civilians, who did not need much encouragement to flee as the militia advanced.

Like its former ally and current enemy, the Army leadership did not want to hand over power before the war and has no intention of handing it over after the war. However, unlike its enemy, it has de facto authority, so it was easy for a member of the (ruling) Military Council, Lieutenant-General Yasser Al-Atta, to issue threats against the civilian forces and accuse them of being unfit to rule, because they are undemocratic parties.

The transitional period in Sudan began with great hopes, and an alliance that included the military component (the Sudanese Army and the RSF), along with the Forces of Freedom and Change (civilian parties supporting the revolution), then it expanded to include the Juba Peace Movements (the Darfur armed struggle movements that fought the regime of Omar Al-Bashir, and for which the RSF was established to confront). Then, the alliance began to disintegrate due to disagreements within the Forces of Freedom and Change, and then the peace movements sided with the military component to overthrow civilians. Following this, the military component was divided against itself due to the war, and the position of the peace movements disintegrated, split between supporting the Sudanese Army and calling for an end to the war and neutrality.

The Army’s faltering in the war led to the spread of the phenomenon of arming civilians, which the Army is trying to control by getting the popular resistance under its control, so that it they operate according to its commands. Meanwhile, there are voices rebelling, as they believe that the formation of civilian militias for armed resistance must be separate from the Army, to avoid repeating the previous course of the war and its failed military operations.

We are, therefore, facing a massive arming operation, without a comprehensive political vision, in a war in which crimes have been committed and documented by international human rights institutions, such as ethnic massacres committed by the RSF and the militias allied with it, and aerial attacks carried out by the Army. A Human Rights Watch report issued weeks ago documented the violations committed by both sides of the war, and a quick look at social media sites shows dozens of videos of crimes that their perpetrators proudly document, such as the RSF’s mutilation of the body of the Governor of West Darfur, or videos of army soldiers slaughtering militia soldiers and celebrating with severed heads.

These, and other matters, cannot be resolved by a resolution, nor will a ceasefire agreement change them. Weapons spread among citizens, the absence of a political vision for the war, the governance of the State and the aftermath of the war, the accumulation of conflicts, and revenge among tribal components already living in a society fighting over scarce resources, are all issues that make the prolongation of the conflict likely. Therefore, international mediation must not only force the two parties to sign a ceasefire agreement, but it must also make sure the consequences of the war are contained so that its continuation and escalation are not dependent only on the weapons of both parties.

This article was first published in Arabic on Al-Araby on 17 February, 2024

READ: Pope Francis appeals for an end to Sudan’s civil war

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Monitor.

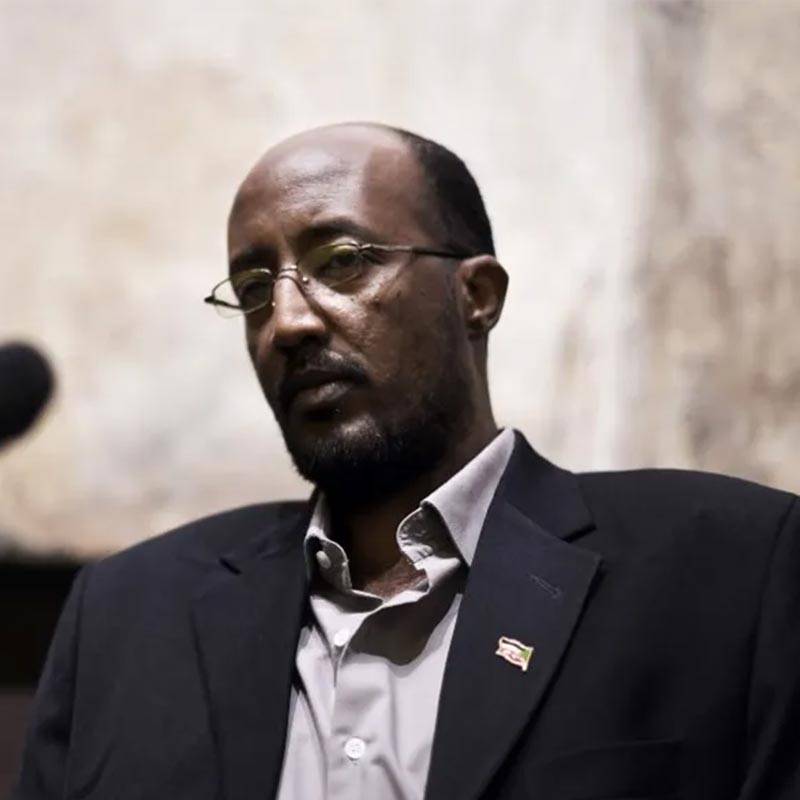

![Chairman of the Sovereignty Council of Sudan, Gen. Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman al-Burhan (L) and Deputy Chairman of the Sovereignty Council, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (R) in Khartoum, Sudan on September 22, 2021 [Mahmoud Hjaj/Anadolu Agency]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/burhan-dagalo.jpg?fit=920%2C613&ssl=1)