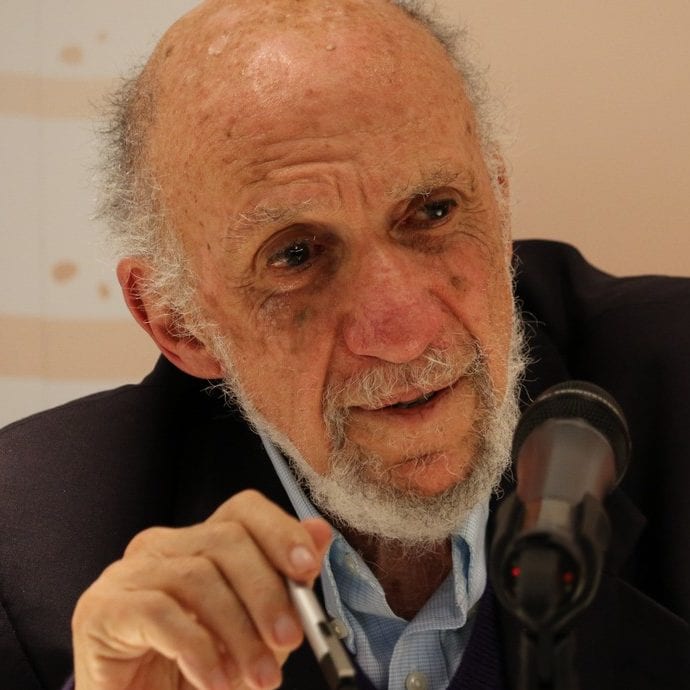

This is part one of our exclusive interview with former Turkish Foreign Minister, Prime Minister and Chairman of the Future Party Ahmet Davutoglu, about his new book ‘Systemic Earthquake and the Struggle for World Order: Exclusive Populism versus Inclusive Democracy’. Using the analogy of a devastating series of earthquakes, in the book, Davutoglu provides a new theoretical approach, conceptualisation and methodology for understanding crisis in the post-Cold War era.

The interview is conducted by Richard Falk, the former United Nations Special Rapporteur on ‘the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967’.

Read part two here – Intellectual and political background of the ‘Systemic Earthquake’

1. You were a prominent figure in academic circles before you entered political life. What prompted you to become a politician?

Whatever field we work in, the unavoidable fact is that we live in a certain space and flow of history. Our existence is defined and limited by the dimensions of time and space. If you are an academic in the social sciences, especially international relations, the influence of these space and time dimensions are felt even more deeply. In a sense, they form an existential framework for your own test tube.[i] Theoretical academic studies beyond the test tube draw one into the reality that exists within it; the conclusions one reaches within this reality start influencing one’s academic work’s theoretical perspective.

This intellectual dialectic between academic theory and socio-political reality also applies to me. My journey between these two fields has been a dynamic process rather than a single, sudden decision. I presented my doctoral dissertation in comparative political theory, later published as Alternative Paradigms[ii] in June 1990, two months before Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in the year the Cold War ended. History’s rate of flow has accelerated here in the Middle East. In a sense, the time/space dimension of our ontological existence has been reshaped.

It was in this context that I wrote articles criticising the End of History hypothesis that claimed that far from gaining pace, the flow of history, when it came to ideas, had actually slowed to a virtual halt; a theory that gained popularity at that time and found adherents in Turkey as well. In these articles I stressed that we should not be fooled by overly optimistic visions as the Cold War came to an end; on the contrary, we were in a far more intense philosophical-political crisis in which decision-makers in Turkey, a country that lay at the centre of all these shifts, needed to be prepared for all kinds of surprises and alternative scenarios. People took a closer look at my views in the wake of developments in Bosnia, which gave Turkey and the world a psycho-political shock. I rejected offers to enter Turkish politics in the 1995, 1999 and 2002 general elections – offers that came during the establishment of new political parties as well. I said I would remain in academic life with a view to pursuing academic studies, seeking to make sense of all these processes and would only be able to offer theoretical advice.

However, it sometimes happens that a person’s own work has a transformative impact on that person’s own life as well. Within a short time of its publication in June 2001, my book Strategic Depth, which analysed regional and global post-Cold War developments and specified Turkey’s strategic position in this new historical context, made a widespread impact in universities and military academies. This led me to accept an invitation to act as chief advisor to the then-prime minister, Abdullah Gül, and later Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. This invitation reflected the change of government in 2002. At the time, Turkey faced three huge issues that would determine its strategic future: the Iraq War, the EU accession process and the Cyprus negotiations.

For seven and a half years I served as chief advisor. This period involved me in a large number of policy processes responsive to these three overall challenges, a few noteworthy examples of which are mentioned in the book Systemic Earthquake. For Turkey and for me, it represented a transition from theory to practice, as well as from scholarship and teaching to politics. Because of my determination to get back to academic life, I respectfully turned down Prime Minister Erdoğan’s suggestion that I be included as a parliamentary candidate with a possible ministerial post after the 2007 elections. The reason I gave for declining was that I intended to return to academic life soon after the elections.

The main factor behind my decision to finally enter into politics was the closure case brought against the AK Party (the Justice and Development Party). The case was initiated about eight months after the party’s overwhelming victory with 46.6 per cent of the votes in the July 2007 general elections – a result that was impressive in the Turkish multiparty context. I regarded this case as a declaration of war against democracy in my country, which amounted to a virtual coup attempt. At that point, I went to see Prime Minister Erdoğan and told him that I would not hesitate to take part in politics at a time when our democracy was under threat, and that I was ready to assume any duty to protect democracy. In response, I was appointed as foreign minister in May 2009 and prime minister in August 2014.

In a nutshell, two principal motives prompted my longer-term involvement in political life: the moral untenability of staying aloof from the practical side of the history, of which I was trying to make theoretical sense, and a sense of democratic responsibility to my country and people as they found themselves at the centre of a turbulent historical process that was gaining ever-increasing momentum, and was challenging the leadership of the country to minimise risks and take advantage of opportunities.

2. This makes me wonder: even with such strong motivational factors, was it difficult for you to make the transition from the academy to the government, having resisted the call for so long? Abandoning teaching and scholarship? Making political compromises in the course of shaping policies and reaching decisions?

Being an academic is not just a profession, but a way of life. You can adapt to changes in your life, but you cannot totally abandon an intellectual calling. Taking on political decision-making roles may limit academia’s field of operation, but cannot erase its nature as something integrated into one’s personality. This limitation is related to the fact that these two areas call for different psychologies and methods, with respect to ethical and professional qualities. The academic life requires pure freedom. The moment one starts self-censoring, one’s freedom of thought evaporates. Yet the diplomatic/political field consists mostly of process management, a process that requires tact, discretion and a certain amount of secrecy. If one discloses one’s views and assessments to the public with an academic’s degree of freedom, one will eventually lose the ability to manage these processes, as well as the confidence of colleagues in government.

This difference in method led me to stop publishing and media activities, including works that were ready for publication, when I assumed duties as chief advisor and ambassador, and started getting involved in diplomatic processes. After continuing my university lectures for about two years, I stopped my teaching activities as well. It seemed to me that my frequent absences abroad in connection with Turkey’s European Union (EU) accession negotiations were imposing unfair burdens on my students.

None of these adjustments meant that I entirely abandoned my identity as an academic, which was very much part and parcel of my personality. There were times when I turned diplomatic/political meetings and even mass campaign rallies into lectures, without being aware of doing so. There were also times when I took refuge from the pressures of diplomatic/political activities by writing and reading. In this context I also took great pleasure in intellectual discourse with counterparts who shared an intellectual/academic background that went beyond the normal diplomatic process. I would also make a point of visiting bookstores in the cities where I found myself, taking full advantage of gaps that allowed me some free time during even the most critical diplomatic talks. Knowing of my proclivities, ambassadorial colleagues involved in our overseas trips would locate the best bookstores in the cities we were visiting, and then make arrangements sensitive to the fact that I might pop out from meetings at any moment to satisfy this book-craving impulse of mine.

All this gave me a deeper understanding of the reason why Ottoman rulers became proficient in some area of handicrafts or fine arts: Süleyman the Magnificent, like his father, in the art of jewellery making, Abdul Hamid in carpentry, Selim III in music, and almost all of them in writing poetry. After intense all-day diplomatic/political activities, it is almost impossible to fall asleep as the issues being discussed agitated my mind to such a degree that sleep became impossible, or it even happened that my dreams would often continue the discussions of the previous day. In such circumstances, the best way to relax is to take refuge in a favourite habit or hobby that will divert you from an intense daily rhythm. So, I would often make a late-night visit to my library before going to bed, or spread books out over my desk after getting the required briefings on long-haul flights and after everyone had gone to sleep, resting my mind and soul by reading and writing. I wrote Civilizations and Cities, published a month after I left the prime ministry, in these intervals during my many long flights.

But no matter how much effort I devoted to making up for what was lacking, I still missed teaching and scholarship. In time, I saw more closely that there are no more loyal friends than books and no more valuable investment in the future than students. When I became foreign minister, diplomats who had worked with me in my capacity as an academic and chief advisor carried on calling me “Professor-Hodja” instead of “Minister” out of habit, which acted as pleasant reminders of the life I had partially left behind. When they apologised for their apparent faux pas, I told them that all posts and positions are transient, but teaching and academic work endures. And today, after I have left my government experiences behind, I would like to reiterate the fact that for those who love it and do it justice, academic work, which is a quest for truth, endures and is invaluable.

Politics is ultimately a process of rational negotiation that, by its nature, requires certain compromises. Nevertheless, it remains vital that these political imperatives should not contradict your fundamental beliefs and/or encroach upon your personal integrity. In a sense, politics is the art of being able to adapt ideals to reality, values to interests and principles to solutions. As a scholar who attaches importance to personal integrity, I have faced some severe tests in this regard during my public life. When I found that this process of adaptation was in general no longer possible, I chose to leave the prime ministry, rather than compromise my personal integrity. In light of this personal experience, I advocate more strongly than ever an understanding and a practice of politics that accords priority to personal integrity. I have never swayed from this approach to politics or the lure of political life, and never shall.

3. I understand that returning to a scholarly life may not have been such a wrench. Nonetheless, do you miss the experience of exercising political influence? You have recently established a new party, Future Party. How do you now envision your future in Turkish politics?

The first thing to say is that my decision to leave the prime ministry did not follow an election defeat or the end of a term limit. On the contrary, it was taken about six months after winning the most overwhelming election victory (49.5 per cent) in the history of Turkish democracy. My decision reflected my principal focus – to prevent differences of view over principles within the party, and the administration of the state to rupture political stability in the country. I also wanted to avoid conflicts of authority between offices of the state over the proper shape of the constitutional order, from turning into a crisis of state. You can imagine how tormented I was in the process of making this decision.

There are two main reasons, to do with my perspective on political and academic life, why the onset of such a sudden and disheartening process did not have a traumatic impact on me. The first, is that I have never seen politics as a career field; on the contrary, I see it as a field of accumulated experience and mission unfolding on the basis of the authority granted by the people. In other words, I have always seen government service and leadership not as permanent property, but as something temporarily entrusted to politicians in the name of public order, to be terminated in the event that the public interest so requires.

The observations I have made during my political life have truly shown me that for those who aim to gain status, money and prestige after becoming a politician, politics begins to take on the characteristics of an ontological field that must on no account be abandoned. Autocratic tendencies develop on just such a psycho-cultural connection between ontology and politics. Seeing the beginning and end of politics as the ultimate career brings about the permanence and sovereignty not of values, but of a status. In a sense, this is to see the concept of glory, which was an inherent value in Roman political culture, as a human condition that has been cleansed of this value.

Secondly, I already had a field of mental and intellectual activity that I loved and that made politics meaningful to me. This is why I have had no adjustment problems, in spite of having made an unplanned and unforeseen return to academic life in the wake of a distressing process. The day I announced my resignation I went back to my natural habitat – my library. I focused on half-completed projects and published a book within a month. I published six more books within two and a half years of my resignation, and participated in several national and international conferences.

There was no contradiction in carrying on my publication and conference activities while my political activities continued, even after my resignation. I took care to do my best in both areas, which required two different psychologies. As I stated at a press conference, announcing my decision not to participate in the 24 June parliamentary elections had two distinct and complementary meanings for me – although I was now focusing on my academic work, I had not left politics.

I continued to follow developments in the political domain closely with regular daily briefings. Just as in academic life, certain habits gained in political life persist. You feel responsibility whenever you see negative developments in your country. I, as a former prime minister and former chairman of the party, expressed my concerns and opinions to relevant authorities on different occasions behind closed doors – whenever I had deep concerns regarding the rising populism and polarisation in our society, limitations imposed on democratic rights, stagflation in the economy, spread of corruption and extensive mistrust to judicial system. When these sincere observations and suggestions were not taken into consideration, I prepared and issued a manifesto after the local elections on 31 March 2019, on the need for extensive reforms in the party and state administration. The party administration decided to expel me and my five other colleagues from the party, rather than to understand our concerns and suggestions. There was no other choice for us, but to establish a new party. The main philosophy and objective of the Future Party is to implement inclusive democracy as set forth as my core political vision in the Systemic Earthquake and the Struggle for the World Order: Exclusive Populism versus Inclusive Democracy. The founders’ board of the party composed of 152 leading personalities, represents all ethnic, sectarian and religious segments of the society. For instance, for the first time ever in Turkish politics, representatives of religious minorities (Armenian, Greek and Assyrian citizens) became members of the founders’ board of a party.

My most important realisation in all these endeavours, is that I have felt no change in my sense of duty to my country and people. I feel this not only as an academician and politician, but as a citizen. I have consistently regarded this obligatory feeling not as a question of office or position, but as one of principle and morality. What is important for me is to try my hardest to fulfil the needs of each moment.

Moreover, one cannot split a person’s identity according to the activity in which they are currently most involved. The principles, feelings and objectives that have guided me as an academician or a politician are the same. In personal transitions of this kind, those who look at life on the basis of a “divided self” psychology may encounter adjustment problems. In contrast, there is no question of such psychological tension for those who see their areas of work as reflections of the same “self” situated in a different time-space dimension.

4. In writing Systemic Earthquake, did you benefit from your own earlier scholarship, particularly Strategic Depth, as well as from your recent political experience?

Absolutely. Systemic Earthquake is posited on a unique synthesis of these two experiential legacies – one mainly theoretical, the other practical. With respect to historical background and global culture, the perspective of comparative civilisational analysis that I used in Alternative Paradigms, is reflected in this work as well. However, the initial theoretical work on which Systemic Earthquake is directly based, is a paper entitled Civilisational Transformation and Political Consequences that I presented at an International Studies Association congress in March 1991, in the immediate aftermath of the Gulf War, and published in 1994 as a book. In this paper, I argued that contrary to the claims of the End of History hypothesis, the ongoing process going forward was not the end of history, but a comprehensive civilisational transformation in which fresh elements introduced by globalisation were shaking the basis of conventional modern philosophy, and the revival of traditional civilisational basins that would change the Eurocentric concept of world order. Working from these premises, I foresaw that first of all tensions would arise from the reawakening of historical factors as a natural consequence of this transformational process. From this perspective, I anticipated there would be a transition from a unipolar world, to a balance of powers system that itself preceded humankind, finally entering a new phase through the birth pangs of change in the axis of civilisation. Refreshed with new elements, the theoretical framework I depicted at that time also played a role in my subsequent works.

In Strategic Depth, published ten years after this paper in 2001, I attempted to examine the geopolitical elements of the comprehensive transformation, then under way in relation to the previous ten years of political developments, and thus define Turkey’s strategic position within these new global and regional configurations. Looked at from the perspective of the framework in Systemic Earthquake, Strategic Depth was written with a view to analysing the 1991 geopolitical earthquake. Systemic Earthquake maintains this theoretical line of interpretation through its analysis of the security (2001), economic (2008) and structural (2011) earthquakes. In this sense, the book was reflective of my academic identity and accumulation of knowledge and experience.

Strategic Depth came from the pen of an academician without any diplomatic experience, Systemic Earthquake reflects the intensive diplomatic and political experiences of someone who had served for seven and a half years as chief advisor to the prime minister, five years as foreign minister and two years as prime minister. In this context, Systemic Earthquake reflects a method and style that includes both these sources of accumulated experience. From this perspective, the inclusion of intensive historical and theoretical analyses in the same framing as political/diplomatic experiences, may challenge the reader with respect to the proper alignment of theory and practice.

5. Which political leaders have influenced you the most? Are these the ones you most admire?

In fact, the life of every leader who has combined historical processes with their own personal quests offers a very serious transfer of experience for anyone keen to draw its lessons. Looking at the lives of great leaders from this perspective, I have found unique instructive qualities in each of them, in terms of human nature, philosophical/intellectual background, historical process and social networks. During my academic life, I designed two courses for particular student groups with this background in mind: first, the intellectual/historical relationship between great intellectual movements that had an impact on humankind and comprehensive political transformations establishing a new order, and secondly, the relationship between intellectual and political leaders who had played a role in the development of national strategies.

It is not right to reduce leaders to a single category in terms of the factors that gave them an enduring place in history, or to evaluate them as individual personalities separate from one another. Leaders in different categories attracted my attention for various reasons, and I tried to learn from their varied experiences and particular talents. The most fundamental lesson to be drawn from the lives of leaders who have pioneered a new order by forging a link between the general flow of human history and the social/historical context in which they live, is the transformative and order-forming power of visionary leadership that recognises and accepts no limits or obstacles. Such leaders include Alexander the Great, who unified almost all of the ancient civilisational basins around a single order; Caesar, who made Rome the centre of a world order by leading to assume a role and reality beyond being a Mediterranean state; Caliph ‘Umar, who, together with a pioneering society without any great experience of governance, led a new order by rapidly spreading a new faith to all the ancient civilisational basins from Iran to Egypt; Mehmed the Conqueror, who established a new order by uniting state traditions drawn from the depths of Asia with the Roman tradition of political governance; and Napoleon, who, through his victories and defeats, had such a profound impact on a Europe being reshaped in every aspect around the system of values, given historical force by the French Revolution.

On the other hand, the most important lesson taught to us by leaders who had an order-restoring impact in periods of major transformation, is the need to establish harmony between the vision being pursued and the actual historical reality in critical transformative processes. In this leadership group I would include Marcus Aurelius, who restored the Roman order in a cosmopolitan context around Stoic thought against Germanic attacks; King Alfred the Great, who led the unification of Anglo-Saxons fragmented by Viking attacks, thereby achieving an English identity; Saladin, who achieved a crucial act of consolidation by uniting many elements of the East, whose order had been deeply challenged by the Crusades; Cardinal Richelieu, who laid the grounds for the era of Louis XIV by uniting France, at that time undergoing a process of ethnic and sectarian disintegration, around a common language and idea of national identity, in spite of the fact that both he and the country were Roman Catholic and therefore owed a form of allegiance to an authority other than the French King (i.e. to the Pope); Bismarck, who pioneered the unification of Germany on the basis of the identity of a modern nation-state, managing in the process to transcend the fragmenting impact of the Thirty Years War that had endured for some two centuries; Lincoln, who ensured the emergence of a United States of America united around shared values from the wreckage of the American Civil War; and Atatürk, who founded the Republic of Turkey by leading anticolonial independence movements after the First World War that destroyed traditional empires.

![European Union flags [File photo]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/European-union-flags-fly-at-european-central-bank-in-frankfurt-germany-500x333.jpg?resize=500%2C333&ssl=1)

European Union flags [File photo]

The lives of three twentieth-century leaders with different civilisational and religious identities (Gandhi, Mandela and Alija Izetbegović) provide us with serious lessons and experiences in terms of their forbearance through all the challenging tests they underwent, especially the tensions between ideals and reality, values and power. They never shirked such tests, although often paying the price of confinement or even death.

In summary, whether you support them or not, and whether partisan or foe, the life journey of every figure who has left a mark on history is replete with valuable lessons. It is crucial that we learn from these lessons in light of our shared humanity, and to transfer this learning as sources of guidance in life and reality.

6. What writers and scholars exerted the greatest influence on your intellectual development, and which were most relevant and important to you in the preparation of this manuscript?

Intellectual development is not a process that emerges in a linear fashion and through specific influences; rather, it is a cumulative work in progress that develops through interaction and internalises itself by reproducing itself at every stage. Therefore, specific, selective and micro-influences may be incomplete.

That said, I would like to list particular names in various fields that I have read with admiration and from whom I have benefited from since the earliest stage of my academic life, to the present day. Among many others, these include paradigm-founders such as Plato, Aristotle, Abu Hamid Al-Ghazālī, Kant and Hegel, who had an influence on intellectual currents carrying their names such as Platonic, Aristotelian, post-Ghazālī, Kantian, Hegelian, etc. Thinkers who played a significant role in the civilisational interaction such as Al-Fārābī, Ibn Rushd and Ibn Sīnā. Thinker-statesmen such as Cicero, Seneca, Nizām Al-Mulk, Thomas Moore, Ahmed Cevdet Pasha, Khayr Al-Dīn Tūnusī Pasha and Sa‘īd Halim Pasha, who endeavoured to establish a sound relationship between intellectual theory and political practice, experienced the tension inherent in this struggle, and in most cases paid a heavy price for it. Leaders like Marcus Aurelius, Winston Churchill and Alija Izetbegović, who produced substantial intellectual works in addition to leading their countries. Historians like Ibn Khaldūn, Arnold Toynbee, Fernand Braudel, Marshall Hodgson, Fuad Köprülü, Halil İnalcık and Kemal Karpat, who used inclusive methodologies while adopting a holistic approach to human history. Political philosophers such as Machiavelli, Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose writings so brilliantly reflected the characteristics of the political culture in which they lived and who had a profound impact on later periods. Modern philosophers/ theoreticians such as Edmund Husserl, Max Weber, Hannah Arendt and Eric Voegelin, who exhibited horizon-expanding approaches in modern thought in their development of conceptual frameworks; and intellectuals/academicians who adopted multidimensional approaches so as to contribute to civilisational interaction, by transcending settled exclusionary molds such as Muhammad Iqbal, Lewis Mumford, Malik bin Nebi, Edward Said, Ernest Gellner, Ali Mazrui, Immanuel Wallerstein, Şerif Mardin, Fred Dallmayr, Richard Falk and Johan Galtung.

Systemic Earthquake is the product of blending the theoretical knowledge I have accumulated through a process of filtering the intellectual works I have studied in the fields of comparative civilisation studies, political history, political sociology, international relations and international political economy.

7. In general, do you learn more from scholars with whom you agree or from those with whom you disagree? Can you give any examples?

In fact, the objective and simultaneous recognition of opposites facilitates learning and correct reasoning. Understanding is a prerequisite for developing an interpretative framework. Even if you end up disagreeing with a person or an idea, you must first understand it correctly. In a sense, understanding something requires an accurate grasp of its opposite. In the words of an old Turkish proverb, “things exist through their opposites.” This is the dialectic of existence. One cannot meaningfully adopt or defend any idea or viewpoint without a proper understanding its opposite. Thinkers with whom I disagree have thus contributed to my accumulation of knowledge as much as those with whom I agree.

I can give an example from the time I was writing my doctoral dissertation in the field of comparative political thought. I was undertaking a comparative study between Niccolò Machiavelli and two thinkers, one who lived in the same historical/cultural basin as Machiavelli (1469–1527) but at a different time, the other who lived around the same time but in a different historical/cultural basin. The first was Rome’s Stoic emperor Marcus Aurelius (121–180) to whom Machiavelli makes reference, the other was Kinalizāde ‘Alī (1510–1572), whose lifespan overlapped with Machiavelli’s and who wrote a book dedicated to an Ottoman Pasha (Semiz ‘Alī Pasha, during the rule of the Süleyman the Magnificent) on the relationship between politics and morality.

Reading Machiavelli’s The Prince, which places power at the center of things and links moral principles to power, Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, which deals with state governance in relation to the moral teachings of Stoic philosophy, and Kinalizāde ‘Alī’s Akhlāḳ-ı ‘Alāī, which puts the principles of affection, morality, and justice at the center of politics, together, made it possible for me to better understand all three of them.

When it came to the relationship between morals and politics, I always felt closer to Marcus Aurelius, whose use of power was seen by Machiavelli as an exception in the relationship between the use of power and morality,[iii] and Kinalizāde ‘Alī than to Machiavelli. However, this did not lead me to conclude that Machiavelli was entirely wrong. My opposition to Machiavelli was over the issue of what kind of a future a person might expect in a world where every leader’s approach made morality subservient to power. However, in terms of the aspect of power that is related to human nature, my better understanding of Machiavelli also provided me with a more realistic context for power-oriented political relationships. In addition, a deep reading of Machiavelli gave me a clearer vision of how psychological factors related to human nature could produce moral deviations, which helped me to develop a kind of warning reflex when engaged in the practice of politics.

I still feel an affinity with Marcus Aurelius and Kinalizāde ‘Alī, who were trying intellectually to create the moral basis for expansive imperial orders in political terms, and I have learned a great deal from them. However, I have learned as much from Machiavelli’s work, which consists of advice given to the eponymous Prince with a view to consolidating his power in a fragmented Italy, even though I cannot on principle espouse his views, because learning is not about agreeing but understanding. Everything that allows one to understand is of value as an object of learning.

8. In a world of sovereign states, is it possible to have a moral foreign policy? What role should respect for international law and the authority of the UN play in developing national policy, especially with respect to security concerns?

We may talk of three different types and areas of relationship in assessing the reciprocal actions of nation-states: shared destiny, common interests, and conflicting interests. The area of shared destiny, especially with respect to ecological issues, transcends territorial boundaries. Countries that share the same ecological destiny in the same geography are expected to cooperate on ecological issues even if they are in dispute over most other issues. In this sense, national security becomes a subcomponent of ecological security because, as the book emphasizes, one cannot possibly achieve national security in the absence of existential security. Nation-states that come into conflict over short-term interests or matters of prestige in these kinds of long-term matters over our shared destiny lay the ground for a shared catastrophe that will negatively impact everyone.

The area of common interests between nation-states relates to the existence of a sustainable peace and order that will enable them to coexist. In this sense, there is a direct relationship between national, regional, and global order on the one hand, and peace and order on the other. Respect for borders envisioned under international law and the development of common policies against terrorism and nuclear proliferation may be appraised in this context.

However, conflicts of interest between nation-states are an intrinsic aspect of international relations in spite of areas of shared destiny and common interests. And when a serious conflict of interest arises, the fundamental issue is the existence or lack of rational crisis management, as well as sophisticated diplomatic knowhow.

![Peacekeepers attached to the UNDOF in the Israeli-occupied Syrian Golan Heights [File photo]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/UNDOF-Golan-Height.jpg?resize=920%2C613&ssl=1)

Peacekeepers attached to the UNDOF in the Israeli-occupied Syrian Golan Heights [File photo]

The logic of raw power is more and more becoming the organizing principle of major international powers in the conduct of international affairs. This is rather new, because both during the imperial era and ideological competition between socialism and capitalism (liberal democracy), power was accompanied by moral claims irrespective of whether these claims were genuine or not, the imperial powers predicated their scramble for power and authority on moral justifications. Likewise, both socialism and capitalism laid claim to legitimacy based on their contention that their ideological programs better fit humanity’s needs and progress than did that of their ideological rival.

In recent years, there is a decoupling between power and moral claim. Trump represents the crystallization of this trend – power for the sake of power. Unless it is reversed, this trend will leave many fundamental questions of humanity unanswered. A question that this trend will face is whether it is tenable to have universal organizations without universally agreed-upon principles and values underpinning it? Unfortunately, decoupling of power and values and power and principles bodes ill for the course of human progress.

In the event that the UN performs its mission for international order within the framework of international legal norms and the practitioners of international law inspire confidence on the question of treating nation-states equally in terms of their shared destiny and common interests, it becomes less likely that nation-states will come into severe conflict while pursuing their individual interests. The current tendency of tensions between nation-states rapidly to morph into crises and wars stems from the international order’s failure to inspire such normative confidence.

9. Do you think that the world map will look very different in a hundred years?

History reflects the dialectic of change and the sustainable order reflects the harmony of the continuity. The future is shaped through the interaction of elements of change and continuity. Those who defend the order by reference to the permanence of the status quo based on conjunctural maps cannot predict or anticipate the dialectic of historical change; those who get lost in the volatility of geopolitical maps shaken by ongoing earthquakes fall into the trap of chaos while imagining they are directing, or at least, controlling change.

While the change in the geopolitical map created by a geopolitical earthquake that struck approximately thirty years ago has still not achieved legally grounded stability, claiming that the same map will still be relevant a hundred years from now detaches history from the dynamic of change. The question is not whether there will be change or not, but how it will be directed. An unprincipled and opportunist approach that provokes change in line with its own interests will pave the way for new destructive processes. These will also likely engulf the advocates of such an approach, while a principle-based, visionary approach in managing the birth pangs of change will lead to a new order with far better prospects of viability.

In addition, the head-spinning pace of human mobility and technological innovation is likely to lead to the replacement of a territorial and space-dependent perception of the current world map with the shaping of a space-transcendent perception of the world map, especially when we appreciate the fact that this momentum is set to accelerate even further in the coming century. In such a process of paradigmatic change, non-conventional maps such as demographic maps, ecological maps, and cyber-communication maps will be as influential as territorial political maps of the world; it is a virtual certainty that world order will be dynamically reshaped on this multidimensional basis, but in what patterns cannot be yet discerned.

10. In addition to law and international public opinion, should ethical principles shape policies? How to balance military necessity against civilian innocence in combat situations?

It is essential that ethical principles shape policies. An understanding of politics that is free of ethical principles ultimately gives rise to an environment in which the rule of the jungle prevails in national and international relations, leaving humankind to face an undesirable future. The alignment of ethical principles and policies is critically important, especially in relation to international humanitarian law.

The exponential increase in the destructive capacity of weapons technology has enormously amplified the imbalance between military capacities, military objectives, and civilian losses unrelated to the objectives of combat. When it comes to destructive capacity, human history has gone through three stages with respect to types of weapons as underlying technology-based conflict and now stands on the threshold of the fourth.

![A Turkish soldier gives a candy to a kid after Ras Al Ayn's Tell Halaf village was cleared of militants, as part of Turkey's Operation Peace Spring in Syria on October 19, 2019 [Behçet Alkan / Anadolu Agency]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/20191019_2_38832209_48620286.jpg?resize=920%2C613&ssl=1)

A Turkish soldier gives a candy to a kid after Ras Al Ayn’s Tell Halaf village was cleared of militants, as part of Turkey’s Operation Peace Spring in Syria on October 19, 2019 [Behçet Alkan / Anadolu Agency]

The fourth stage, at the threshold of which we now stand, involves a destructive capacity that is both supra-spatial and supra-temporal in such a way as to risk the eradication of the future of all humankind. Albert Einstein’s well-known statement that “I do not know with what weapons World War III will be fought, but World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones,” a prediction that is used to demonstrate the level that this destructive capacity has reached, indicates the total destruction inherent in a mechanism of war detached from ethical control. As I stressed in the book I wrote immediately after the Cold War,[iv] the ethico-material imbalance that most strikingly manifests itself in the destructiveness of war technology constitutes one of the most critical dimensions of the comprehensive civilizational crisis that we are going through. Since then, the concept of the ethico-material imbalance that I employed to show the gaps between political mechanisms and moral values has grown wider in almost every field.

In addition, the advent of remote-controlled drones in conflicts and robots developed without moral responsibility and accountability has produced serious issues of ethical control even in conventional wars and limited military operations. In this context, there is now a pressing need for a reconsideration of international conventions on these issues.

[i] I am referring here to Julian Huxley’s description as the paradox of a social scientist living in his own test tube. Julian Huxley, Man in the Modern World (London: Chatto and Windus, 1947), 112–31.

[ii] Ahmet Davutoğlu, Alternative Paradigms, Lanham: University Press of America, 1994.

[iii] Nicolo Machiavelli, The Prince, Great Books of the Western World, Mortimer J. Adler (ed. in chief) Chicago: Encyclopedia Brittanica, 1990, vol. 21, pp. 27-28.

[iv] Ahmet Davutoğlu, Civilisational Transformation and the Muslim World, K.L.: Quill, 1994, p. 18-21.