This is part two of our exclusive interview with former Turkish Foreign Minister, Prime Minister and Chairman of the Future Party Ahmet Davutoglu, about his new book ‘Systemic Earthquake and the Struggle for World Order: Exclusive Populism versus Inclusive Democracy’. Using the analogy of a devastating series of earthquakes, in the book, Davutoglu provides a new theoretical approach, conceptualisation and methodology for understanding crisis in the post-Cold War era.

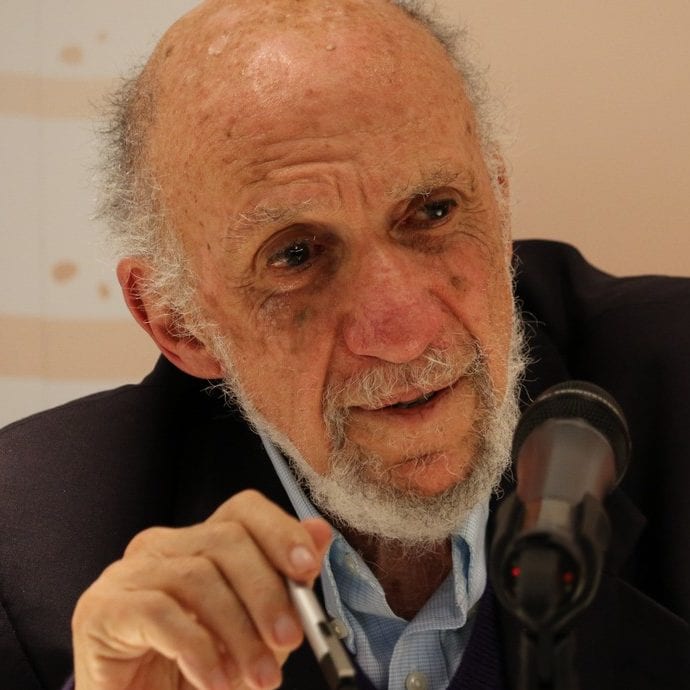

The interview is conducted by Richard Falk, the former United Nations Special Rapporteur on ‘the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967’.

Read part one here – The future of the world order: Exclusive interview with the former Prime Minister of Turkey

11. You propose “inclusive democracy” as a desirable political goal. How does this differ from “electoral democracy”? Should the values and procedures of inclusive democracy also inform the structures and practices of global governance?

One of the most fundamental areas of tension in thinking about democracy today lies in this very critical difference between inclusive and electoral democracy. And the source of the threat to Europe, which is seen as the cradle of democracy, by extreme-right and racist currents that use electoral democracy as a base from which to impose an exclusionist political agenda after winning an election through all kinds of populist rhetoric, also reflects this dilemma. The fact that Marine Le Pen got through to the second round in the French elections and that racist parties are on the rise in Holland and Germany makes it clear that if these political currents win an election, even by a small margin, the entire concept of citizenship in constitutional societies will be eroded and fall victim to a polarization based on a binary division. Drawing a distinction between “real” French, German, British, Dutch, Italian, etc. people and “newcomers” or “strangers” means the destruction of inclusive democracy by electoral democracy. An electoral democracy that eradicates inclusive democracy will lead to the revival of the historical experiences of extremism undergone in Europe between the two World Wars.

The only way to overcome this tension is to view electoral democracy and inclusive democracy not as alternatives but as complementary to one another. The process of electoral democracy takes precedence over the principles of inclusive democracy. As a process, electoral democracy is a sine qua non for a real democracy, a real imperative. A lack of respect for the national will expressed in an election means the eradication of the principal gains of democratic history. But inclusive democracy is an absolute prerequisite in terms of enabling the grounding of a real, self-regenerating democracy. Otherwise, as happened in the period between the two World Wars, when a government formed on the basis of the unqualified nature of the one-time results of electoral democracy breaks away from inclusive democracy, electoral democracy is likely to be rendered meaningless, and totally undermined.

In this context, electoral democracy constitutes the infrastructure of a real democracy; inclusive democracy its load-bearing pillars. Without electoral democracy inclusive democracy cannot be realized; without inclusive democracy, electoral democracy degenerates, and cannot flourish through self-regeneration. Electoral democracy makes up the mechanics of democracy, inclusive democracy its organic structure. In other words, electoral democracy is hardware, inclusive democracy is software.

A constitution based on the human rights and human dignity serves to guarantee the complementary relationship between electoral democracy and inclusive democracy. In societies where constitutional consensus and conventions are in crisis, the risk is that inclusive democracy gets hollowed out by coups or populist ideologies, and that electoral democracy becomes a mechanical legitimating instrument of government. The coupism in Turkey and Egypt, which disregards the results of electoral democracy, and the rising extremist trends in Europe to use electoral democracy to destroy the most fundamental elements of inclusive democracy, threaten the future in equal measure.

These principles also apply to global democracy and governance. A UNSC system that fixes five permanent members in place without any electoral process while revolving non-permanent members are selected by means of elections involving the other 188 member states has minimal inclusivity while its electoral attributes reflect an ineffective oligarchic concept of governance. There is also a manifest need for new conventions to protect the rights of countries and indeed all humankind.

To sum up, and as emphasized in various sections of the book, the most pressing condition for a new world order today is the emergence of a new philosophical and implementable set of principles for inclusive national, regional, and global governance.

![A protest calling for climate change on 1 June 2017 in Paris, France [kellybdc/Flickr]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/2017_7-1-Paris-Protest.jpg?resize=920%2C613&ssl=1)

A protest calling for climate change on 1 June 2017 in Paris, France [kellybdc/Flickr]

12. World order continues to be state-centric in its fundamental character – that is, with respect to the formation and implementation of policies on matters of global concern – yet the problems (climate change, nuclear weaponry) seem global in scope. How can the pursuit of national interests be reconciled with the realisation of global interests?

It is normal that the international system is state-centric. I think the problem here isn’t that the international order is state-centric. The real problem lies in the definition of sovereignty. Because the division of labour at multiple levels – local, domestic, regional, and global – requires a new understanding of sovereignty backed up by the political will of leaders. Given the hyper-interdependency of the international system and human destiny, the state can’t operate on the basis of the traditional Westphalian conception of the nineteenth- and even early twentieth-century understanding of the sovereignty. The concept and institution of sovereignty is in dire need of redefinition. In a revisionist understanding of sovereignty, the national level shouldn’t be set against the global level. They should be framed in ways that complement each other. In this respect, we should contemplate a new form of sovereignty, which is multi-layered, inclusive, and driven by commitments to the collective good.

From such a perspective, the nation-state is not a competitor of the international order but its building block. What is important is that these building blocks have a strong basis of legitimacy within themselves and that they have the flexibility and dynamism to accommodate the diverse concerns of the international system’s nation-states. When I spoke at international platforms about matters of universal concern like climate change and nuclear weapons, I always mentioned the need to develop first a global awareness and only then to posit this awareness in an international normative framework and convention. On the question of awareness, it is an absolute condition that issues related to the ontological existence of humankind supercede all kinds of concepts of individual state interests, because (and I emphasize this in the book) the political existence of nation-states is impossible without ontological existence. Ignoring the threat to humankind’s common security posed by the excessive pursuit of individual national security presupposes an Armageddon psychology and apocalyptic scenarios.

The most effective method to eliminate such scenarios is the application of legal norms developed in this context, without exception. For example, the inconsistency of certain countries who regard nuclear weapons as a threat but ignore the nuclear armament of other countries in the same region shakes trust and confidence in the international system as a whole and paves the way for every country to take its own measures to arm itself regardless of the threat to collective wellbeing, even survival. It is impossible to overcome individual conflicts of interest in an environment where the interests and concerns of certain nation-states are regarded as more important than those of others.

In this context, it is essential to establish a strong and consistent connection between consciousness of humanity and of citizenship. This can only be achieved through the spread of communications between global civil society and national civil societies and can be realized by the emergence of psychological spheres of influence that transcend the outlook of nation-states. It should not be forgotten that threats such as climate change and nuclear arms whose destructive impact cannot be restricted to the legal and spatial boundaries of nation-states cannot be resolved only by negotiations limited to nation-states.

13. In this conversation you have talked about how your career has made the shift from academic to political, then back to academic life and now back again to the political domain after establishing a new party. Do you consider this to be your final professional destination? Or would you welcome a future rhythm that involved alternating periods of government service and scholarly life? In this sense, would you describe your present state of mind to be best described as “post-political” or “pre-political,” or some combination?

A person making his or her own decision about personal final destination is like the “end of history” claim for humankind, a claim that I have opposed in this book and on every possible occasion. As Demetrius strikingly said, “An easy existence untroubled by the attacks of Fortune is a Dead Sea.”

If one’s final destination were known, the excitement and energy of life would be lost. Perhaps the most important thing that makes a person happy, even when they cannot know it, is their own final destination. The only thing I know at this point is that neither my personal future nor that of humankind is going to be “an easy existence.” This doesn’t mean I have a pessimistic view about the future. Quite the reverse, the new challenges brought by those “attacks of Fortune” also require fresh paradigmatic initiatives. With the dynamism engendered by these challenges, it is certain that neither my personal future nor the general future of humankind is going to be that “Dead Sea;” the challenge is to find key wavelengths and frequencies able to surf successfully through the continuously rising flow of history, and thereby reach their target. The “future rhythm” you refer to in your question will also to some extent be the work and challenge of this surfing exercise.

I have always approached post- and pre-conceptualization with caution. Every post-situation harbours its own pre-situation. In other words, in the process of history every post-situation is shaped in the womb of a pre-situation. As Wordsworth said, “The child is father of the man.” Could the conditions of the post-Cold War period have been formed without the process of change that occurred in the final years of the Cold War?

This also applies to personal journeys and quests. The academic work Strategic Depth that I wrote in the pre-political period of my life defined my behaviour in the political phase of my life, while my post-political academic works have been shaped by the experiences derived from that same political phase.

When I left the prime ministry, I never said I had left politics behind. In any case, after such a high-profile past in politics, one can’t really remain outside of political debate even if one says “I’m out.” Although I have tried to avoid political polemics in this period, I have remained on the political agenda with both positive and negative comments. So, there is a clear difference between becoming post-governmental and post-political. Regardless of official titles I was and will always be political.

At the early stage of writing Systemic Earthquake in 2017, I was a parliamentarian of my previous party, when the book was published in January 2020 I became Chairman of a new party, Future Party. As I have underlined in my books, history continues to flow personally, nationally, and globally. I do not think there will be a pre- or post-era in my life. But, there will be a difference compared to my previous experiences. Unlike my decision not to write when having an official position which I followed faithfully during my public services as Chief Advisor, Foreign Minister and PM from 2002 until 2016, I am planning to continue my academic publications in the future despite resuming the work of being an active politician.

All these challenges are inherent to politics. But just as one’s personality cannot be divided, nor can one’s life. The key thing is to live an unfragmented life with an undivided integrative personality. One can do this by taking the right steps that bring together the needs of the moment with one’s own conscience. The difference I made in politics came to a large extent from my scholarly past. On the other hand, what is distinctive about my post-political academic works will undoubtedly be fed and influenced by my political experiences. Therefore, I can say that my present state of mind is a combination of both.

As an academician I never underestimated the significance of being a politician, and when I became a politician I tried never to forget my identity as an academician. The first stopped me from getting detached from the reality of the flow of history, while the second kept me from getting imprisoned in constructed conjunctural reality.

14. In contemplating Turkey’s future in a time of systemic earthquake, what sorts of response would you hope to be forthcoming from political leadership and from civil society?

No scholar can ignore the time–space dimension they encounter within themselves and the experiences they have gained as they generate and develop ideas. In that spirit I naturally drew upon the case of Turkey throughout the book and especially in the chapter entitled “Inclusive National Governance.” I believe that the five main principles I considered with reference to the recommended approach to deal with the systemic earthquake are primarily applicable to my own country. In fact, Turkey constitutes perhaps one of the most striking examples with respect to these principles.

![A Daesh sign at the entrance of the city of al-Qaim, in Iraq's western Anbar province near the Syrian border, seen on November 3, 2017 [AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP/Getty Images]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GettyImages-869813922.jpg?resize=500%2C333&ssl=1)

A Daesh sign at the entrance of the city of Al-Qaim, in Iraq’s western Anbar province near the Syrian border, seen on November 3, 2017 [AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP/Getty Images]

Secondly, Turkey is a remarkable case when it comes to a nation-state’s geopolitical basis, because apart from the one with Iran, none of the country’s borders rest on sound geopolitical ground. The border with Syria cuts through residential districts, the border with Iraq through mountains, and its Aegean border skirts islets and rocks. The risk of suddenly erupting tensions is always present. The main reason for my advocacy of the “zero problems with neighbouring countries” principle from 2002 onwards was the potential that existed to derive an order from these geopolitical abnormalities. Successfully pursued up until the structural earthquakes that occurred in surrounding countries in 2011, this policy saw the establishment of high-level cooperation mechanisms with Russia, Greece, Iraq, Syria, Bulgaria, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Ukraine, and Romania, and the development of relations between peoples through mechanisms such as visa waiver and free-trade agreements that were developed with neighbouring countries. Our 2004 negotiations with Greek Cyprus, and the protocols signed with Armenia in 2009[i] showed our determination to achieve normalization (we did not have diplomatic relations with either state before). Today, one of Turkey’s top priorities is the achievement of stability and peace all along its geopolitically sensitive borders.

Thirdly, the freedom–security balance that forms the basis of political legitimacy needs to be painstakingly maintained. It is crucial that a country like Turkey, which has passed the test of being a democratic country in a high-risk geopolitical environment, does not lurch between freedom and security preferences. The fact that in the face of the global security earthquake in the post-9/11 period that shook the world and tended to detach countries from human rights, Turkey made significant strides with respect to the implementation of human rights and freedoms, which are the fundamental elements of inclusivity, and backed this up with a multidimensional foreign policy, enabled the country to make a regional and global difference in those years.

Fourthly, its young and dynamic demography is both a major advantage and a serious challenge for Turkey. Educating and preparing this young and dynamic population for the future requires a policy of sustainable economic development and fair income distribution. It is crucially important that political leaders, the business world, and civil society generally agree on this issue on the basis of shared, rational objectives.

The fifth point is that Turkey is going through an absolutely critical process with regard to the institutional structure of national order. With institutions developed within a deeply rooted state tradition, Turkey faces the need to rebuild its state architecture as a result of the recent constitutional referendum. In this context, the balance between institutional continuity and institutional restructuring needs to be carefully developed to safeguard democratic expectations.

In summary, Turkey’s geography requires multidimensionality, its history inclusivity. If Turkey takes both these elements into account, the ongoing systemic earthquake will present not only risks but opportunities. Turkey needs to find its own distinctive path at a time when the systemic earthquake has encouraged a global trend towards exclusionary autocracy. The course of historical change is determined not by those who act in line with the general trend on the basis of herd mentality but by those who make a distinctive difference. Even if this difference is not sufficiently appreciated in the heated midst of the process, its influence will make itself felt over time. This is how to ensure national legitimacy and international prestige.

15. Since completing Systemic Earthquake there has been a continuing trend toward demagogic political leadership, coupled with polarized patterns of governance, in many of the most important countries in the world. Does this trend disturb you? Do you expect it to continue?

The most frequently overlooked element in efforts to establish national, regional and global order is the psychological factor. In a psychological atmosphere in which feeling, emotion, and sentiment overwhelms rational thought, rhetorical radicalism subsumes any shared or common view, tactical steps subsume strategy, and impulses subsume principles. While building sustainable order is all about a set of principles generated by a common mindset and the strategic issues based on them, acquiring and keeping hold of conjunctural power is a tactical question based on impulsive and rhetorical radicalism. The growing trend to demagogic political leadership is the psycho-political reflection of rhetorical radicalism; a polarizing and exclusionary understanding of politics, a reflection of its impulsive radicalism. Like everyone with a worldview that envisions a future for humankind based on equality and human dignity, I am seriously concerned about this development. A number of large-scale wars in the past were triggered by reciprocally impulsive reactions that had emerged from such a psycho-political atmosphere.

However, it is impossible to overcome this disturbing development by getting caught up in a psychology of helplessness in the face of such a wave, or turning a blind eye to the conditions that have led to the wave in the first place. What is needed is an accurate analysis of the psychological grounds that have been thrown up by it and the promotion of a vision of order based on humankind’s shared legacy of experiences with the capacity to generate the global momentum required to create a counter-wave.

![US President Donald Trump delivers remarks at 'Keep America Great Rally' on January 30, 2020 in Des Moines, IA, United States [Kyle Mazza / Anadolu Agency]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/20200131_2_40597934_51682544.jpg?resize=920%2C613&ssl=1)

US President Donald Trump delivers remarks at ‘Keep America Great Rally’ on January 30, 2020 in Des Moines, IA, United States [Kyle Mazza / Anadolu Agency]

16. The Trump presidency has epitomised this trend, which has also led to an ultra-nationalist foreign policy, which exhibits hostility to international law, the UN, human rights, and cooperative approaches to global problems. Does the world suffer from the loss of a more internationalist style of global leadership associated with pre-Trump American foreign policy?

To use the conceptualisation I have proposed in the book, we might say that Trump represents the most extreme slide into strategic discontinuity in US foreign policy that has been experienced with any post-Cold War change of presidency. In every period changes in the international system have necessitated a paradigmatic renewal in US strategy. As the eighteenth century gave way to the nineteenth, and however much the young United States of America appeared to have been excluded from the international Eurocentric colonialist power struggle, the Monroe Doctrine published in 1823 in line with the new state of affairs in the wake of the Congress of Vienna helped to lay the ground for an internal consolidation around republican principles as well as an American continent-oriented consolidation of power far from the influence of monarchical restoration in Europe. Through the nineteenth century, this founding paradigmatic principle, which was enunciated by the fifth US President James Monroe, recognized as the last of the United States’ founding fathers, constituted a strategic basis unaffected by whichever political party the president happened to be affiliated.

As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, the United States, whose economic prowess had turned the country into a leading actor in international economic-political balances, became an international naval power in the context of the Roosevelt Corollary’s more assertive interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine, after which the beginning of the country’s assertion of influence within the international system through the principles laid out in President Wilson’s Fourteen Points indicated a continuum of change in the US strategic paradigm. The fact that Theodore Roosevelt was a Republican, and Wilson a Democrat, never caused any strategic discontinuity in terms of the United States’ status as a leading actor. The proactive strategy of Franklin Roosevelt (a Democrat, unlike his Republican cousin Theodore) in the Second World War put the United States center stage in the post war international system. Even in this paradigmatic transformation, the “American Century” was one of consensus and continuity in terms of twentieth-century economic-political, geopolitical, and geo-cultural balances in the strategy’s principal elements.

However, as the world moved into the twenty-first century, and in spite of having emerged as the victor of the Cold War, the United States’ strategic paradigm proved unable to forge a coherent and consistent whole. George H. W. Bush’s “new world order,” Bill Clinton’s “humanitarian interventionism,” George W. Bush’s “pre-emptive strike,” Barack Obama’s “multilateralism,” and Trump’s “America First”-oriented conceptualisations contained elements of incoherence and discontinuity as well as being in part reactions to their predecessors’ policies.

In a nutshell, while the nineteenth century was the European, and the twentieth century the American century, the twenty-first, a “Global Century” shaped by the dynamic elements associated with globalization, has a complexity that is hard to comprehend, disentangle, and resolve by reference to just one geographical location. While a multi-dimensional, multi-actor period such as this (in the book we call it the “multiple balance of powers system”) requires a far more sophisticated approach, the US slide towards a one-dimensional, self-centric approach characterized by Trump’s “America First” slogan, with its disregard for international law and norms, is not sustainable either in terms of the functioning and operation of the international system or of US interests.

17. The rise of China represents the most dramatic geopolitical development in the twenty-first century. Do you think that the rise of China is on balance beneficial or detrimental to the future of world order? Do you believe China can fill the global leadership vacuum created by the Trump withdrawal of the leadership role that the United States played since 1945? Could you envision a more multi-polar global leadership emerging in the future? Or possibly a post-Trump US/China joint leadership? Or is a new Cold War more likely with the United States on one side and either China or Russia, or some combination, on the other?

In the post-Cold War era, especially after the 2008 global crisis, China’s attainment of a leading position in the world economy was a new state of affairs that represented a test for China itself as much as for the world and the other major powers. During its classical periods, China saw itself as the “civilized center of the world,” even “the world itself”; it possessed a strategic paradigm based on protecting itself from potential threats from the world outside, rather than taking any interest in the external world. The Great Wall of China constitutes the most striking manifestation of this strategic mindset paradigm, which was the product of China’s effort to protect its own world from the that which lay beyond. In this context, except for the Hui-origin Muslim Chinese Admiral Zheng He’s overseas expeditions at the beginning of the fifteenth century, China had no concept of a common order, or working to establish contacts with the non-Chinese world. The Opium Wars, which forced China’s strategic culture to change in the mid-nineteenth century, were essentially waged with a view to discontinuing this strategic resistance. Once again China’s confrontation with modernity took place through the inward-looking Maoist methods identified with the Cultural Revolution.

In the post-Cold War period, China’s ever more rapid integration into the international economy along reformist lines pushed China to change its aloof approach towards the outside world that it had adopted in the traditional and modern periods. Indeed, it would be impossible for a global power with an economic structure integrated into the world economy either to remain outside the world political system or to remain indifferent to developments within it. In this sense, Chinese President Xi’s The Belt and Road Initiative project is not just a sign of economic interdependence. It will also reflect China’s inevitable and growing interest in the field of international politics, including the security of the transport corridors that it naturally requires.

In this framework, the main question is what tools and methods are going to be applied by China to further its interests. From the perspective of China’s traditional stance as well as today’s economic-political balances, a scenario in which China gains the status of guarantor of the global order by itself, by filling the vacuum left by the United States in the wake of Trump’s policies, appears unlikely. The scenario in which China assumes a leadership role in conjunction with the United States risks creating a polarization that could bring actors such as the EU, Russia, Japan, and India together in such a way that this kind of quest for balance would frustrate any such joint-leadership project. The move towards the conditions for a new Cold War with the United States at one pole and China at the other is not a burden that an increasingly complex network of economic relations can carry. It should not be forgotten that the previous Cold War did not take place within the same economic model but only ever between blocs of countries with different economic models. It would be very hard to forge an enduring Cold War in a world where the same or similar economic models are interacting in a global economy. In this context, the most likely scenario is a “multiple balance of powers” system with growing Chinese economic-political influence but in which the thematic, sectoral, and geopolitical basis of international relations may be dynamically determined at any moment.

Yet it would be wrong to restrict China’s distinctive and distinguishing features to the realm of economic-political balances in this new period. Every change that occurs in China, home to one-quarter of the world’s population, will also be decisive in the cultural order that includes the scientific and technological elements of the international system. China’s growing influence in the restructuring of the global cultural order will be accompanied by the transformation of the modern, mainly Eurocentric, cultural order. Therefore, this “multiple balance of powers” system’s soft (cultural) aspects need to be taken very seriously and all multinational platforms, especially the UN system, need to have a genuinely peace-promoting and inclusive character. As is emphasized in the text of the book, Pax Universale does not need global Caesars followed by self-centric Neros, but rather Marcus Aureliuses from different cultural basins.

![Young boys wear medical masks as a precaution to protect themselves from coronavirus in Kirkuk, Iraq on February 25, 2020. According to the latest reports 4 people infected with Coronavirus in Kirkuk, north of Baghdad [Ali Makram Ghareeb - Anadolu Agency]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/20200225_2_41033461_52499810-1.jpg?resize=920%2C613&ssl=1)

Young boys wear medical masks as a precaution to protect themselves from coronavirus in Kirkuk, Iraq on February 25, 2020 [Ali Makram Ghareeb/Anadolu Agency]

18. Your book Systemic Earthquake writes about ruptures that change the international atmosphere in dramatic and unexpected ways. Do you consider the global spread of COVID-19 virus is or could become such a rupture?

Since we are still living through this pandemic, it is hard to make a definitive judgment that it will lead to a global rupture. However, it is at least clear that COVID-19 is set to be a precursor and test bed for probable global-scale ruptures.

Precursor, because COVID-19 has strikingly shown once again that human destiny flows along a single common river that does not allow for the separation of one continent from another or one religious or ethnic community from another. It is both natural and inevitable that with the acceleration of growing global interaction we shall soon see stronger waves and ruptures that will impact our common future.

Test bed, because the stance taken on COVID-19 will determine the course of subsequent ruptures. Broadly speaking, when it comes to this stance there are two options. The first is that just like quarantining people during the pandemic, societies and countries will tend to quarantine themselves on a long-term basis through inward looking policies designed to avoid being affected by global ruptures. It is extremely hard for this introspective attitude, which I define in the book as a cynical reaction against globalization, to deliver a lasting solution with respect to the impact of global rupture. It should not be forgotten that quarantine is a temporary measure; making it permanent means the end of societal life. Likewise, the long-term nature of the restrictive measures taken by countries to mitigate the impact of the epidemic serves to minimize the positive interaction gains of globalization.

The second possible stance is to move forward once again with a shared global-scale ontological consciousness based on a common concern for the existential future of humanity in the face of this global rupture. This shared ontological consciousness will not have the capacity to develop enduring responses to global ruptures unless it transcends the political and economic interests developed individually by political actors and countries. As we underline in the book, where there is no ontological existence, political existence loses its presence and meaning.

19. This health challenge arises in a historical circumstance in which the world is experiencing trends toward the embrace of ultra-nationalist ideologies and the rise of democratically elected autocrats. Against this background, does the COVID-19 challenge underscore the importance of global cooperation under the auspices of the United Nations?

Absolutely. In order to be able to transform this shared ontological consciousness into a set of global policies, the only tool available to us is the UN, whatever its troubles. Yet if the UN is to be able to carry out this duty, the privileged status it affords to certain countries in terms of their capacity to determine the destiny of humankind needs to be reformed. Having said that humankind needs to move forward with a single and shared ontological consciousness, the current UN structure, based on granting five countries ultimate decision-making status with respect to the political manifestations of this destiny, of its essence runs contrary to this consciousness.

In particular, in the event of ultra-nationalist and autocratic leaders who prioritize their own short-term personal and national interests coming to the fore in these five countries, the UN ceases to be a solution-producing body and turns into a source of problems. In the context of a state of affairs in which these five countries pursue their disparate interests and display mutually polarizing attitudes, it becomes difficult for the UN to mobilize a shared ontological consciousness. The tendency of the US and China to exchange accusations during the COVID-19 crisis has been a cautionary tale. Approaches such as this serve to block the existing UN system and undermine the idea that the UN is the shared mechanism of humanity. Right now, the urgent need is to achieve an inclusive, democratic and participatory United Nations, and to enhance its effectiveness.

20. In a deeper sense, the COVID-19 eruption suggests the limits of our understanding of what the future will bring to humanity. Does this uncertainty about the future make it more essential than ever to govern societies in accord with ‘the precautionary principle’? Does the ecological fragility of world order, combined with its vulnerability to previously unknown viruses, suggest the need for more flexible democracies or does it portend a post-political future for all levels of social and political order?

Yes, ‘the precautionary principle’ can be an important reference point in overcoming the global vulnerabilities and uncertainties associated with rapid technological development and globalization. However, the success of this principle in practice depends on its unconditional and blanket acceptance and implementation by all parties. Otherwise, non-compliant parties may gain a scientific / technological / economic advantage over their compliant counterparts. In the framework of this principle, the manner in which the United States’ failure to ratify the Kyoto Protocol and Canada’s withdrawal from it prevented the World Charter for Nature adopted by the UN in 1982 and enshrined in the preamble of the 1987 Montreal Protocol from achieving its desired effect, is clear. When ‘the precautionary principle’ framework is correctly defined and implemented without exception, it can prevent or at least limit this kind of vulnerability. And for this to happen, an institutional body and mechanism that is not wrapped up in political concerns but motivated by universal principles needs to be established.

The most effective solution to the ecological vulnerability further exposed by the emergence of viruses previously unknown to the world order is the concept of an inclusive and participatory flexible democracy. This concept of democracy must bring with it a fresh political mindset. Perhaps these developments can be seen as a precursory phase towards a new political understanding, rather than a post-political phase. At the beginning of human history too, human beings basically transitioned to the phase of forming a political society by removing the security risks associated with natural life in the most primitive fashion. This time, humanity will have to develop a new global-scale concept of political societal order in order to bring the ecological risks created by humankind’s own hand under control. Although this concept of order appears post-political from the modern political perspective, from the perspective of a political order based on global governance, it could well take the form of a harbinger.

In any case, all these developments show that we are pushing against the limits of current understandings of political order. Humankind will either turn to a new humanity-oriented concept of global governance, or rupture from human values on the wheels of autocratic structures seeking to exploit all these vulnerabilities. Our primary duty today is to strive to forge the intellectual infrastructure of a new humanity-oriented order of global governance.

Indeed, this is the fundamental purpose of this book, Systemic Earthquake.

[i] For an assessment of these negotiations from a third perspective see Hillary Rodham Clinton, Hard Choices, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014, s. 218-220.