Saif al-Islam Gaddafi and Khalifa Haftar are running for the presidential elections scheduled for 24 December, and the controversy that followed added nothing else to the very complex scene in Libya, other than fuelling the fear that these elections will not be a way out of the deepening crisis in this country, as much as it will likely be one of its new chapters.

Waiting to know the rest of the candidates and what will happen in their regard, as well as the results of the appeals that may be submitted by any of the candidates, will not change any of the apprehension accompanying these elections.

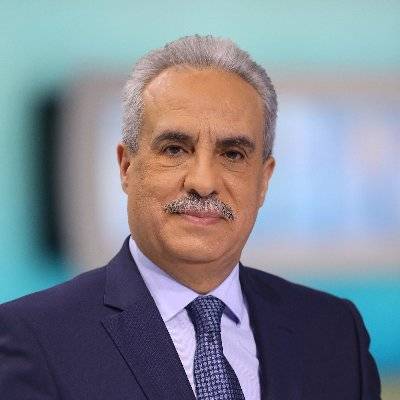

This apprehension was expressed by more than one party, Libyan and non-Libyan. I will mention here what two former international envoys to Libya said. Tarek Mitri said, “everyone wants elections in Libya or claims so, but compromises about power-sharing and holding elections alone do not guarantee the unity of the country and its peace, as it does not replace the unanimity of national goals that prevent quotas, the agreement on a new social contract and the building of state institutions.” Meanwhile, Ghassan Salameh says that “there is no worse harm to democracy than rejecting the election results and trying to undermine them with violence. Examples of this are Iraq and Ethiopia today, and many countries before them, whose losers rebelled against the rule of the ballot box. Therefore, their countries were torn apart in civil wars or slipped into individual rule. Everyone is a loser in a match that ends with the destruction of the stadium.”

The reason for this pessimism is not only the continued division in the Libyan political and security institutions between the east and the west, but also the absence of a minimum political consensus between the conflicting Libyan parties in preparation for going to the polls. There is also the absence of a constitutional basis for these elections legally, as well as a large number of difficult questions that are still pending regarding these elections. Some of these questions were expressed by Hanan Salah, a specialist in Libyan affairs at Human Rights Watch, when she asked, “can Libyan authorities ensure an environment free of coercion, discrimination and intimidation of voters, candidates, and political parties? Since election rules could arbitrarily exclude potential voters or candidates, how can authorities ensure the vote is inclusive? Is there a strong security plan for polling stations? Is the judiciary able to deal promptly and fairly with elections-related disputes? Can election organisers ensure independent monitors will have access to polling places, even in remote areas? Did the High National Elections Commission arrange for an independent, external audit of the voter register?” She answered all these questions by saying, “Given the situation in Libya, this all seems questionable.”

READ: Will the Libyan elections lead to calm or chaos?

With the risk of holding presidential elections without a constitution because this would definitely mean the establishment of the rule of the individual “leader” after a bitter rule in this way for 42 years with Colonel Gaddafi, what worries more is the international interaction with the Libyan crisis, because it shows not only a sharp division between two camps that support one side of Libya at the expense of the other. This is in light of foreign forces and mercenaries who have not yet left Libyan soil. It is also a kind of acceptance of dealing with these conflicting entities between the east and west of the country, only because they are just parties that can be spoken with regardless of their legitimacy or representation, while some harbour a frightening conviction that Libya can only be ruled with an iron fist and the leadership of one man.

Even the Paris conference, which was held recently and attended by the countries concerned in one way or another with what is happening in Libya, was not able to untie the knots of holding the elections or postponing them. It was content with threatening those obstructing them, either people or entities, by imposing sanctions on them even though previous sanctions did not prove their effectiveness, including what was decided by the US House of Representatives under the Libya Stabilization Act.

One of the most dangerous things that Libya could also face is that any questioning of the integrity of the elections or the rejection of their results may lead, once again, to the emergence of a government in the east of the country and another in the west, after this duplication was eliminated with great difficulty through the national unity government headed by Abdel Hamid Al-Dabaiba. There are also fears of the return of the threat to stop the export of Libyan oil again. If foreign forces and mercenaries decide to support this or that party after the results appear, things may become more complicated, and we may even enter into a violent civil war with the presence of problematic candidates such as Gaddafi and Haftar. The attack that took place on some of the headquarters of the High Electoral Commission after the announcement of their candidates only foreshadowed such a frightening possibility, which is further exacerbated by tribal and regional backgrounds and sensitivities.

Could postponing the elections be the solution? No one can be certain of this, but we do know that conducting the elections under the current circumstances is extremely risky, especially since the time is very short to address the problems facing its integrity. Among all the hypotheses, the Libyans are holding their breath, as well as the neighbouring countries and those who love them.

READ: Libya’s former interior minister to run for presidential election

This article first appeared in Arabic in Arabi21 on 17 November 2021

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Monitor.

![People gather to protest against the candidacy application of Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi, the son of former Libyan ruler Muammar Gaddafi, for upcoming presidential election in Tripoli, Libya on November 15, 2021. [Hamza Alahmar - Anadolu Agency]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/20211115_2_50896292_70701323.jpg?fit=920%2C613&ssl=1)