One of the most difficult and dangerous jobs in Israel is to be a Palestinian Arab member of the Israeli Parliament, the Knesset, and for good reason. Such MKs pose the greatest threat to the continuation of Israel’s racist and Apartheid policies and have the power to stop it.

Israel is planning a General Election for membership of the Knesset in April. Its Arab citizens have a chance to boost their ability to undermine racist government policies. That is why “Israeli-Arab” citizens elected to the 120-member Knesset — Christians and Muslims alike — face daily bullying, intimidation and harassment from Jewish MKs. Indeed, Christian and Muslim Israeli citizens experience daily discrimination precisely because of their faith and ethnicity.

Israel has adopted more than 65 laws that specifically discriminate against Christian and Muslim — that is, non-Jewish — citizens explicitly, or are contained within the distorted principles of Israel’s corrupt human rights policies. The racist laws are detailed by the Israeli civil rights group Adalah, the Legal Centre for Arab Minority Rights in Israel.

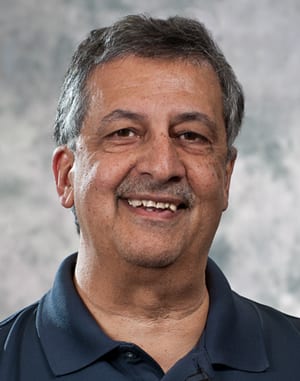

In many cases, peaceful non-violent protests by Arab civilians in Israel are confronted by police officers using tear gas, bludgeons and live ammunition. Over the years, Ahmad Tibi MK, a deputy speaker of the Israeli Knesset who has served since 1999, has been attacked by Israeli police and settlers while protesting against state racism. Tibi was beaten by police last May, for example, when he joined other Israeli-Arab citizens who protested against the relocation of the US Embassy to occupied Jerusalem.

Early elections: Who will dethrone ‘the king of Israel’?

It’s been worse, and many have been threatened with arrest and jail, simply for being critical of Israel’s policies. Jews, meanwhile, can attack Arabs viciously if they use the word “Nakba”; any non-Jews who question Israel’s legitimacy on social media face arrest.

Arabs in Israel are denied equal rights and equal services by the state. Many Israel cities have either passed official policies, as Afula has, or embrace unofficial practices, such as in Gilo, banning the sale or rental of homes to Arabs. Discrimination is widespread and has an impact on education, public services and government support.

Of Israel’s 10 poorest communities, eight are Arab villages. Israel provides financial assistance to Jewish cities and communities but limits government funding to their Arab equivalent. Jewish communities on average get 42 per cent more funding and services than Arab localities.

Yet despite these racist laws, Arab citizens have the power to change Israel; they have the right to vote, but they don’t use it effectively. There are nearly 1.8 million Arabs living in Israel. One-fifth of the population, they are the descendants of the Palestinians who the Zionist militias and nascent state forces failed to expel during anti-Arab violence in the run-up to the creation of the State of Israel in 1948 and its aftermath. The percentage may well be higher as many believe that Israel’s census downplays the size of the non-Jewish population for political reasons.

In 2015, the four major Arab political parties formed a coalition called the Arab Joint List to consolidate their voting power. In response, Israel’s Apartheid government adopted a racist law that increased the number of votes that a party must receive in order to be represented in the Knesset. That figure used to be 1 per cent, but as the Arab vote increases, the threshold has also been increased. In the face of Arab efforts to strengthen their voice, Israel increased it to 3.25 per cent, effectively excluding smaller Arab parties from the Knesset.

What’s more, only “registered” parties can field candidates. In many cases, Israel refuses to recognise Arab parties and the racist media does not report on and thereby does not document such anti-Arab policies. With its smaller population, the 3.25 per cent threshold has a greater impact on the Arab community than it has on Israeli Jews.

READ: Israel parliament votes to dissolve itself triggering an election

Despite the racist laws, the racist policies and the constant harassment, Arabs still managed to have a voice in Israeli politics. In the 2015 elections, the Arab Joint List won just over 10 per cent of the vote and elected 13 members, making it the third largest party in Israel behind the Likud (23 per cent, 30 seats) and the Zionist Union (18 per cent, 24 seats).

The Arabs in Israel could easily increase their number of Knesset seats with a higher voter turnout and thus boost their ability to challenge and change Israel’s racist policies. However, concerns against “normalisation” weigh heavily on Arab minds and Arab voter turnout. Many Palestinian groups inside and outside of Israel oppose “normalisation” and discourage voting in Israeli elections. That needs to change. The de facto ban is based on a high moral principle, but in reality, it has been destructive to Palestinian rights within Israel.

Modest Netanyahu – “I am ready to leave my position tomorrow as prime minister, but I have no one to leave the keys with” – Cartoon [Sabaaneh/MiddleEastMonitor]

Israel’s Arab population needs to stop undermining its own power and act strategically, linking normalisation prohibitions with tactical progressive activism. Israel exists, discriminates against Arabs and occupies Jerusalem. By participating in the state’s voting processes, its Arab citizens could change the status quo. They need to go to the polls in ever greater numbers.

https://www.facebook.com/middleeastmonitor/photos/a.175445796925/10155675484206926/?type=3&theater

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Monitor.

![Dr Ahmad Tibi, Member of Knesset seen at Middle East Monitor's 'Jerusalem: Legalising the Occupation' conference in London, UK on 3 March, 2018 [Jehan Alfarra/Middle East Monitor]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/104A0668.jpg?fit=920%2C613&ssl=1)