The Israeli occupation forces are ethnically cleansing northern Gaza using lethal force. Hundreds of Palestinians have been killed, and many have been wounded. That much is clear to all but the fanatical Zionists. The statistics across Gaza are appalling: 43,340 killed; 102,100 wounded; 11,000 missing, presumed dead.

Palestinians are not simply statistics, though. Behind the numbers are real people with hopes and dreams; families, friends and colleagues. Stories to tell; stories to remember.

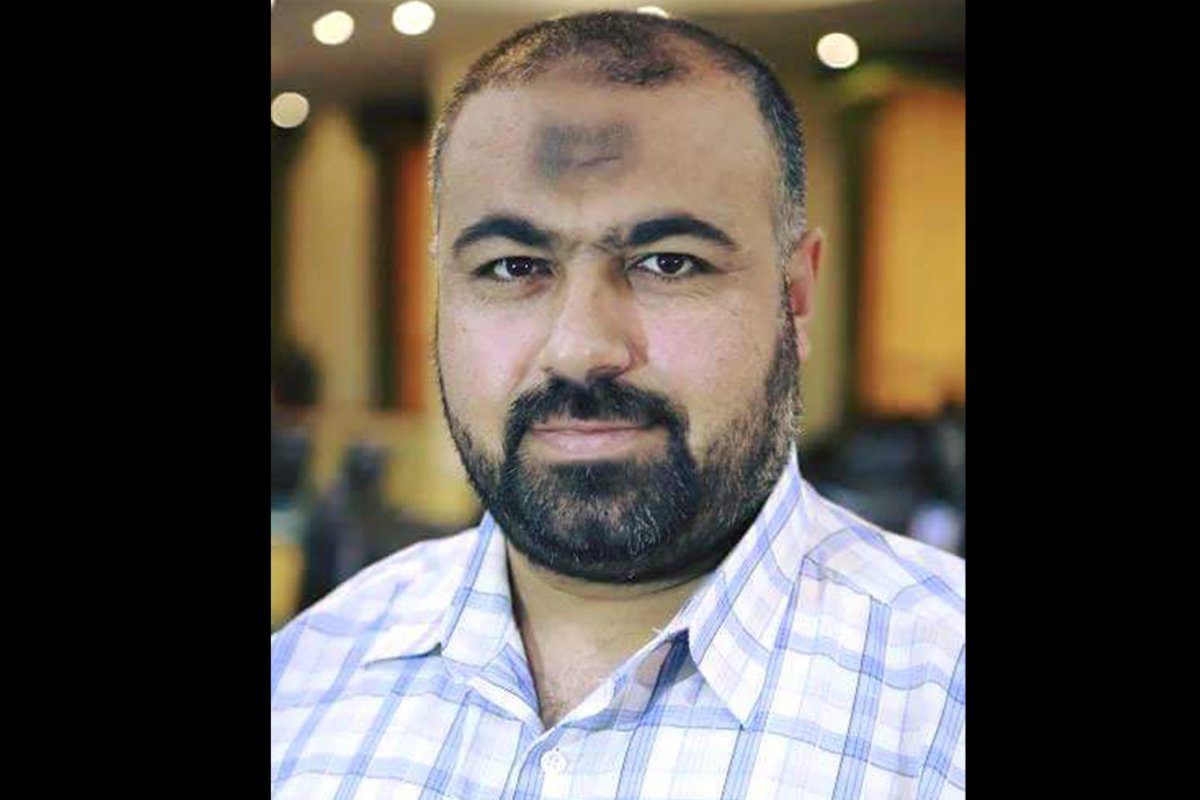

Fadi Shehadeh, for example, saw his wife and son killed when Israel bombed a school being used as a shelter for displaced persons in Jabalia refugee camp. He was forced out of the tightly blockaded camp carrying his wounded daughter on his back.

Now it is 1.30pm in the corridor leading to the operating theatre of the orthopaedic surgery department of Al-Ahly Al-Araby Hospital in Gaza City. The corridor is full of patients and wounded people lying on the floor. A 45-year-old man, one of the walking wounded, is tottering on tired legs, but still trying to clear the way for two nurses moving a bed out of the operating theatre.

The patient on the trolley is an 11-year-old girl with external fixators on both of her legs and a breathing tube fixed to her nose; another tube is coming out of her chest and a third comes out of her belly. The girl is unconscious and the father looks grumpy, but he cheers when the girl opens her eyes and moves them from side to side.

“Who is this girl?” I ask the man.

“This is Lianne,” he replies. “She is the only one of my family to survive a bomb which targeted the shelter in which we sought refuge in Jabalia camp.”

His wife and son were among the 37 killed in the attack, all of them displaced persons.

As he follows his daughter’s bed and the nurses, he raises his hands and murmurs some prayers. “Thanks to Allah that He left one of my children alive and did not leave me alone,” I hear him say.

READ: Israel kills 55 more Gazans as death toll surpasses 43,300

I ask him his name and he replies quickly. “Fadi Shehadeh.”

I know that a big clan with this name live in the northern cities of the Gaza Strip and I had heard that many families have lost loved ones during the ongoing Israeli genocide.

Finding an empty place in the hospital for his wounded daughter took about half an hour. There are patients everywhere: on beds, on trolleys, on chairs and on the floor. The hospital grounds have been turned into cemeteries.

Fadi is exhausted and has relatively light wounds on both of his legs. He thanks the nurses and stands beside his daughter’s bed. He looks at her; she is unconscious. Then he places his right hand with great tenderness on her cheek.

He agrees to speak to me about what happened to his family. I can empathise with him, having lost my own wife and children in this genocide.

“What happened?” I ask as gently as possible. He asks his sister to stay beside his daughter, holds my hand and leads me out of the building.

Outside, he takes a deep breath and begins: “The Israeli occupation forces ordered us to evacuate the school [where they had taken refuge] and gave us 15 minutes to get out. We immediately started to pack our few belongings, but after only five minutes, there was a massive explosion. The school was full of smoke and everyone was screaming.”

He was not hurt. “When the smoke cleared, I looked around and found my wife, my son and my daughter were critically wounded. There were body parts everywhere. I was shocked and felt powerless. All my family members were bleeding; my neighbours were bleeding; my uncle, who is 83 years old, was bleeding.

“Everyone needed help but there were no rescuers because the refugee camp had been under a tight military blockade for 21 days at that time. The ambulance and civil defence services had almost stopped their operations due to the lack of fuel.”

As he speaks, he turns his face away and cries, the tears streaking down his face.

Recalling the tragedy is too much; too painful. With no tissue paper left in Gaza, he uses a small handkerchief to wipe his tears.

“There was a big hole in my son’s belly and his intestines were hanging out,” continues Fadi. “He was motionless. I could see that he was dead. I turned to my daughter and my wife, who were still breathing. My daughter’s legs were both broken and she was bleeding all over her body. My wife also had a big hole in the right side of her belly and another hole in her chest. A student nurse arrived — what a surprise — and checked my son. She confirmed that he was dead, so we left him and fled with my wife and daughter.”

OPINION: Political interests in the age of genocide: Is Europe abandoning Israel?

The student, Niveen Dawawsa, called some people over to help Shehadeh to carry his wife and daughter to hospital. Two people helped them using a donkey cart; its owner had been killed in the Israeli bombing and his body was in the schoolyard.

“We walked all the way carrying my daughter, while my wife was on the cart. We arrived in the hospital two hours after the bombing.” There were far more wounded than paramedics. “Niveen stayed with us and did her best to stop my wife haemorrhaging, but she couldn’t. My wife died an hour later.”

Lianne was still alive, though, but she was bleeding and hadn’t been seen by the paramedics. Niveen helped to stop the bleeding from her legs and belly, but she needed to be examined as a matter of urgency; she needed X-rays of her legs and a CT scan of her stomach. Niveen took Lianne on the donkey cart to the Indonesian Hospital, which is also in Jabalia, where she could ask doctors to look at Lianne.

“The doctors found shrapnel in her belly and decided that she needed urgent surgery to remove it,” Lianne’s father tells me. “Unfortunately, the doctors could do nothing for her because the Israeli occupation forces stormed the hospital and ordered everyone to leave and move to the south of Gaza.”

That was the day that the Israeli occupation forces attacked Kamal Adwan Hospital, the Indonesian Hospital and Al-Awda Hospital. All of them are in Jabalia, but serve all the northern cities. The Israelis killed and wounded a number of patients and paramedics and destroyed vital lifesaving facilities during the forced evacuation of the hospitals.

“Me and two of my brothers were detained along with hundreds of people, including displaced persons, paramedics and patients,” adds Lianne’s father. “I told an Israeli soldier that my daughter was wounded and I needed to evacuate her to Gaza City. “They let me go and ordered me to carry Lianne on my own. I did, but when I passed through the military checkpoint east of Jabalia, the soldiers shot me in the leg. I fell down with Lianne, but a soldier shouted at me and ordered me to stand up and carry her despite my injuries. Thanks to Allah, I was only slightly injured so I could carry on. That’s how I carried my daughter from the Indonesian Hospital to Al-Ahly Al-Araby Hospital in Gaza City.”

There was no comfortable, well-equipped ambulance to take this little girl to hospital; only her father, on his back.

Her pain with two broken legs and a stomach wound must have been excruciating. Despite everything, he made it to Al-Ahly Al-Araby Hospital. What must have been going through his mind as he carried his badly wounded little girl on his back having just watched his wife die and seen his son killed?

“At last, we reached a relatively safe place and my daughter found doctors to treat her. She had surgery on both legs and shrapnel was removed from her intestines. She needs several operations, but for now that’s all that can be done.”

Fadi Shehadeh has come to the end of his story and turns to go back into the hospital to be with Lianne. The little girl wounded in a deadly Israeli air strike is safe for the time being, with her father and aunt by her side.

I thank him for sharing his story with me. It’s one more to add to the growing roll call of heroic efforts and determination by Palestinians facing genocide in Gaza.

I have now shared Lianne’s story with you. Remember her name, and remember her father. Remember their story. They deserve nothing less.

OPINION: Genocide is embedded in US diplomacy

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Monitor.

![A view from the area after Israeli airstrikes on Jabalia refugee camp in northern Gaza, on October 31, 2023. Palestinians, including children killed in a series of Israeli airstrikes on Jabalia refugee camp, Interior Ministry spokesman said on Tuesday. [Stringer - Anadolu Agency]](https://i0.wp.com/www.middleeastmonitor.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/AA-20231031-32589103-32589102-ISRAELI_ATTACK_ON_RESIDENTIAL_SQUARE_IN_JABALIA_REFUGEE_CAMP.jpg?fit=920%2C663&ssl=1)